Source: Photo by George Lloyd | Painting: © Oki Chu - reproduced with permission

Manga artist Oki Chu brings ‘low brow’ psychedelic art to Okachimachi

- Tags:

- Illustrator / low-brow / manga artist / Oki Chu / painter

Related Article

-

Yokohama-based Canadian painter Sylvia Haw’s Comme des Fleurs exhibition invites you to bloom to your full potential

-

A letter from my former self: a Twitter user makes some surprising changes growing up

-

Manga artist discovers that his cat’s fur pattern is a readable barcode

-

The Moody, Mysterious World of Pixel Artist, Illustrator and Videographer APO

-

“I couldn’t hire a model”: Photo of manga artist in his 40s wearing the tee he designed goes viral

-

Japanese Manga Artists and Illustrators Welcome 2019 With Awesome Original Cards

For the past six years, artist Okinaka Yoshinari, better known as Oki Chu, has been focussed on hosting other artists’ work at mograg, the small gallery he runs in Okachimachi. But now he’s taking centre stage for a few weeks, with a solo exhibition of what he calls his ‘low-brow art.’

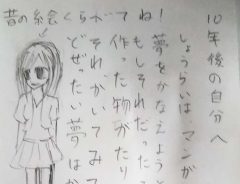

“Self-portrait by Oki-chu” | Photo by George Lloyd / Reproduced with permission from © Oki Chu

Why ‘low-brow’? I asked when I went to see him at mograg. “In other countries, ‘art’ is mainstream, and my kind of ‘low brow’ art is underground,” he explained. “But manga and anime are so dominant in Japan that mainstream art has become a subculture.”

“As a result, a lot of Japanese people think of ‘art’ as being difficult. I think of my work as being somewhere in the middle, between manga and art. I want my gallery to be a place where ordinary people have an opportunity to enjoy cool art.”

Photo by George Lloyd / Reproduced with permission from © Oki Chu

Oki Chu gives me a guided tour of the pictures on the walls and I ask him how he comes up with his outlandish creations. “I like surrealism and automatism,” he tells me. “Automatism is a technique where you empty your mind and just start drawing lines on the page with a pencil without thinking.”

“Then I look at what I’ve drawn, and think, “Oh, this looks like a hand,’ and that’s when I start drawing with the pen. That’s how I do all my pictures. I don’t start out with any particular subject in mind. I discover the subject as I go along, drawing on the archive of images from comics and games in my head.”

Photo by George Lloyd / Reproduced with permission from © Oki Chu

Oki Chu is from a village in Mie prefecture. He started drawing when he was a kid, with his biggest influence being Nintendo and the games available on the Famicom video gaming console. Super Mario came out when he was in the first year at elementary school. He was really impressed by the illustrations on the box and started creating stories for Mario in his head.

He got his love of monsters and dragons from the work of Toriyama Akira, the creator of Dragonball and Dragon Quest. Another big influence was Mizuki Shigeru, creator of GeGeGe no Kitarō and masterly depictions of yōkai (traditional Japanese monsters, ghouls and goblins).

Photo by George Lloyd / Reproduced with permission from © Oki Chu

Oki also loves the intricate, delicate paintings of Edo era master Itō Jakuchū 伊藤 若冲. “He was painting in a kind of digital style 250 years ago. When I first saw his work, I could see the connection with Nintendo.”

Oki studied art at Seian University of Art and Design 成安造形大学 in Shiga prefecture. He didn’t learn much while he was at university, but his course left him with plenty of free time, which he spent making short films with his friends.

It was while at university that he first came into contact with foreign comics such as French bandes dessinées, and particularly the work of comic book creator Moebius. He also took a liking to the black and white illusions created by the Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher.

Photo by George Lloyd / Reproduced with permission from © Oki Chu

Many Japanese artists seem politically disengaged, so a painting of a rampaging farmer holding a banner proclaiming ikki 一揆 – uprising - grabs my attention straight away.

“In the old days, ee ja nai ka was big in Mie prefecture,” he tells me. For those unfamiliar with the history of rural subversion in Japan, ee ja nai ka ええじゃないか was a kind of carnival, in which communal religious celebrations overlapped with political protests. They occurred all over Japan, particularly at the end of the Edo period, when the Meiji Restoration turned the old world on its head.

“Instead of taking up weapons, people danced, and while they were dancing, someone would get into the local merchant’s storehouse and steal the rice,” he says with a laugh. “It always reminded me of the flower power movement in the 1960s - a kind of ‘revolution through dance.’

An Edo era depiction of ee ja nai ka festivities. | Kawanabe Kyōsai, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

And what about the haru, natsu, fuyu 春夏冬 (spring, summer, winter, skipping fall) banner that he’s holding? “They used to have banners like these outside shops in the Edo period. It was a running joke with shopkeepers” (春夏冬 is meant to be read akinai, which has three possible interpretations. It can mean ‘never give up’ or ‘always look on the bright side’ 飽きない, or "business" 商い, but it can also mean "no fall" 秋ない).

A common theme in Oki’s work is a delight in brains and guts. I ask him if the grotesque is popular in Japan. “Well, it’s certainly popular with a lot of the artists I know. I like guts - the internal organs. Brains and stomachs are great to draw. They’re so colourful!”

“I took part in a group show in China a while back, and I noticed that there was no grotesque in the Chinese underground art scene. You can’t see images like this in China, but I think most Japanese are fine with it.”

Oki Chu’s exhibition "3Ø2Ø." runs until 29th November.

Prints from the exhibition start at ¥9000 unframed. The gallery also stocks a range of stickers, mugs, T-shirts, and comic books by a range of underground comic book artists.

mograg Gallery is open 13:00 - 20:00 daily and closed on Sundays. You’ll find it at 1-5-1 Moto-Asakusa in Taito-ku, just opposite Shin-Okachimachi Station.