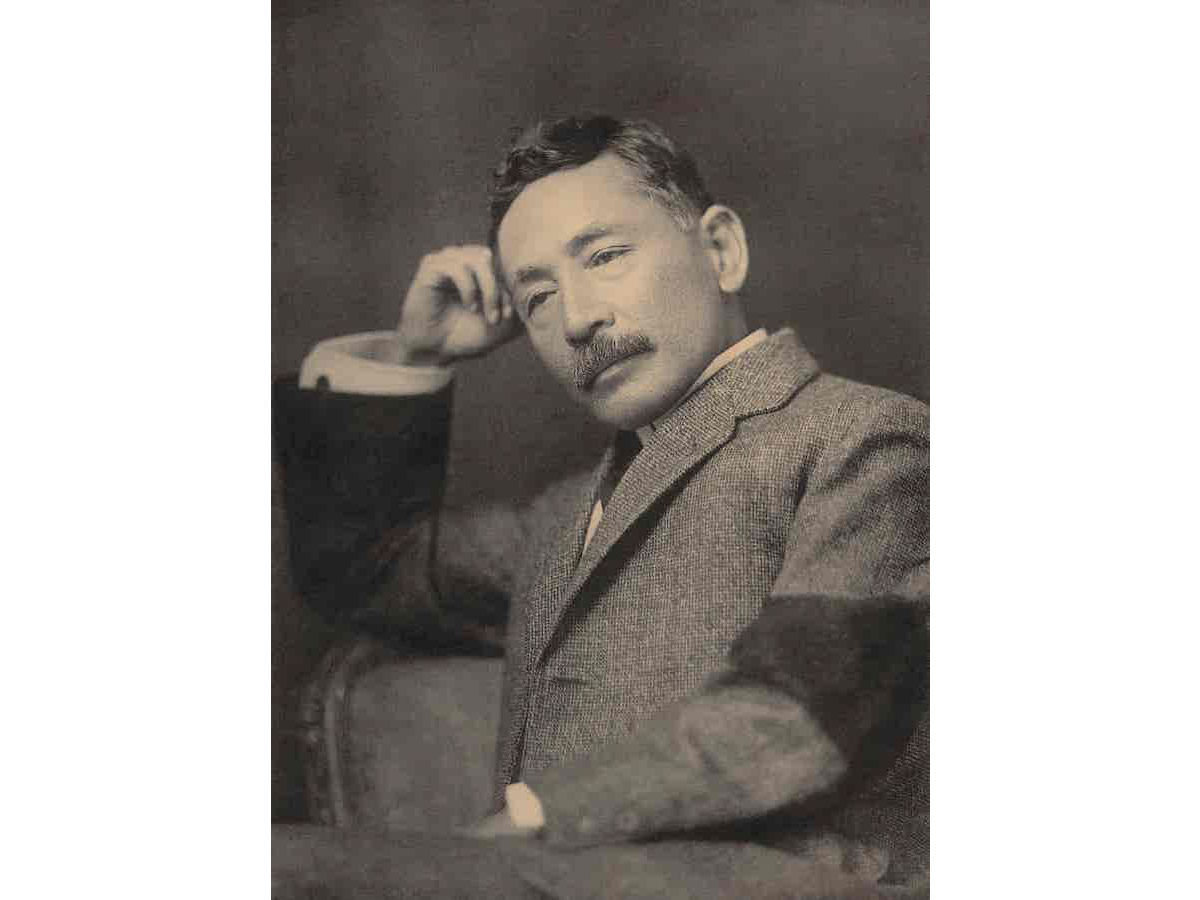

Source: Store Norske Leksikon, "Natsume Sōseki", CC by SA 1.0

Natsume Sōseki in London: “a dog thrown into the company of wolves.”

- Tags:

- Japanese Literature / London / modernity / Natsume Sōseki

Related Article

-

Akutagawa Prize Winner Li Kotomi: Updating the Face of Japanese Literature One Novel at A Time

-

Japan’s Most Legendary Samurai Duel Now Available As Premium Wrist Watches

-

You Can Now Download 300-Year-Old Ancient Japanese Literary Texts For Free!

-

These Two Cats Have A Wonderful Relationship With Their Window Washer

-

Japan Travel Guide: A visit to the Kamakura Museum of Literature

-

Kimono: Timeless Treasures on Display at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum until 6/21

Natsume Sōseki 夏目漱石 is one of Japan’s most famous novelists, and the only one to grace a banknote. He is credited with pioneering the synthesis of European literary modernism and traditional Japanese narrative. He was also one of the first Japanese people to live in London and his descriptions of the city offer a remarkable insight into how perceptions of Japan and the West have changed over time.

Natsume Sōseki was born in Tokyo in 1867 and studied in the English department of Tokyo Imperial University. He was only the second student to major in English and he proved a devoted student.

Sōseki was enthralled by the promise of the modern world. He believed that the poverty and oppression that many of his countrymen had to endure would only end when feudal Japan faced up to its backwardness and took lessons from the West.

After being awarded a scholarship by the Japanese government, he arrived in London in October 1900 to study for a degree in English Language and Literature at the University of London.

Passengers atop an Omnibus passing through the City of London c.1900. ‘The man on the Clapham omnibus’ was a byword for Joe Public in those days. | whatsthatpicture from Hanwell, London, UK, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sōseki met several well-known British writers, including Thomas Carlyle, while he was in London. He also got to know the handful of other Japanese in the city, including the man who would go on to establish Mitsui Trading, with whom he often went to the theatre.

By all accounts, life in the world’s biggest and most dynamic city made Soseki profoundly unhappy. He wrote that the two years he spent in London were the most unpleasant of his life. “I led a most miserable life among the English and felt like a dog thrown into the company of wolves.”

His unhappiness is hardly surprising when you consider the near-poverty Sōseki lived in. The cost of living in London was three to five times higher than in Tokyo at the time and he spent most of the little money he had on books, mostly second-hand (he would return to Japan with 500 volumes). He led a peripatetic existence, for he was forced to move lodgings five times, an experience that gave him a precious insight into the lives of working-class Londoners and their landlords in south London neighbourhoods like Camberwell, Brixton and Clapham.

All the same, there is good reason to wonder if Sōseki wasn’t exaggerating when he likened the English to “wolves”. Records show that the landlady of the house in Clapham where he eventually settled cared about him a great deal. The ‘man on the Clapham Omnibus’ may have taken a shine to him too. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was concluded in 1902, and many Britons admired the Japanese for their supposed ‘pluck’ in going to war with China in 1894. Some even called Japan ‘the Great Britain of the Far East.’

On the other hand, contempt for non-Europeans was widespread in London and Sōseki is likely to have met with plenty of cold shoulders. The British Empire was at its zenith in 1900, and even the lowliest of Queen Victoria’s subjects regarded Britain’s economic might as proof of his inherent moral superiority to foreigners.

The house in Clapham, south London, where Sōseki lived. | Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0

Sōseki was in London to see Queen Victoria’s funeral procession through the city in February 1901. It must have seemed a rare moment of calm in the city. In his letters home, he admitted finding it hard to adjust to the inhuman rhythms of modern city life. He describes a soulless city, in which any sign of human pleasure or spontaneity had been snuffed out in the name of material progress.

He was amazed and moved by the regimentation that had been foisted on the city’s workers. London seemed to be governed by the clock, with none of its people able to escape its mechanical grip.

Eighteen months after his arrival in London, Sōseki found himself confined to his room by poverty and ill health. He suffered from neurosis, and particularly towards the end of his stay, rarely left his lodgings in Clapham.

He missed home. He remembered Tokyo with fondness and missed the spontaneity and relative freedom its people enjoyed. Turn of the century Japan might have been chaotic and unruly, he reflected, but at least it was recognisably human.

A crowd watching a free show in Asakusa, Tokyo in 1904. | Tekniska museet, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sōseki returned to Tokyo in 1903 and became a lecturer in English Literature at the First National College, subsequently replacing Koizumi Yakumo (Lafcadio Hearn). He embarked on his writing career in earnest and went on to make his name as a pioneer of the ‘I’ novel, whose introspection and ambiguity were a world away from traditional Japanese literary conventions.

He wrote several books about his two years in London: Recollections, The Tower of London and Within my Glass Doors. The city also features in Spring Miscellany and London Essays, Letters from London and Diary of a Bicycle Rider.

Sōseki’s recollections of the time he spent in London are interesting for the perspective they offer on Japanese perceptions of the West in the Meiji period. "Perhaps the modern world wasn’t all it was cracked up to be?" he wondered. Yet he knew that Japan had no choice but to modernise if it was to avoid becoming another western colony.

Sōseki’s recollections of big city life at the turn of the twentieth century can only chime with modern urbanites. We might feel bewildered by the pace of change in the world’s megacities, but he felt the same about life in Victorian London.

Railway workers at Clapham Junction in 1900. | The Underground Map, CC by SA 2.0

What is striking is not his bewilderment, but the role reversal that has taken place between ‘us’ and ‘them’ since Sōseki’s day. Westerners often regard the Japanese as having been dehumanised by modern life, turned passive, robotic, inexpressive and imitative by the megalith that is Japan Inc. But Sōseki described the people of turn-of-the-century London in similar terms and even missed the ‘unruly chaos’ that he associated with Tokyo.