- Tags:

- cooked nature / Nature / raw nature / relationship with nature

Related Article

-

Awesome 360° Panorama Tour Site Lets You Explore Some Of Japan’s Most Gorgeous Areas In Style

-

This Artist Paints Gorgeous Landscapes On Tree Logs To Spread Her Message

-

See Tokyo (almost) as nature intended at the National Institute for Nature Study

-

5 “Nature-Made Tunnels” In Japan Too Beautiful Not To Walk Through

-

Illustrator’s charming key chain design gives you a travel companion to paint with nature

-

Walk Through The Stunning Autumn Leaves Of Kyoto’s Famous Arashiyama Sightseeing Course

The idea that Japanese people have a particularly close relationship to nature, which westerners have somehow lost, is deeply ingrained in how the Japanese perceive themselves.

The idea first took hold during the Meiji period (1868-1912), when Japan was forced to re-define itself in relation to the West. Naturally, Japanese thinkers were sensitive to how westerners perceived them, and they weren’t averse to appropriating orientalist imagery from the West when it suited them.

Characteristics that were supposed to suggest the weakness of Eastern peoples were redefined as strengths. Some Japanese thinkers accused westerners of having become estranged from nature, in contrast to the Japanese, who were supposed to have stayed true to it. Love of nature became synonymous with being Japanese.

Carles Tomás Martí / © Flickr.com

It’s certainly true that ‘nature’ is a social construct; how we perceive the natural world is not fixed, but changes according to the kind of society we live in. In Japan, ‘nature’ is not usually seen as the opposite of ‘culture’, as it tends to be in the West. Instead, nature is understood to oscillate between two extremes. At one extreme is ‘raw’ nature. At the other is ‘cooked’ nature, which is to say, nature modified by humans for human purposes.

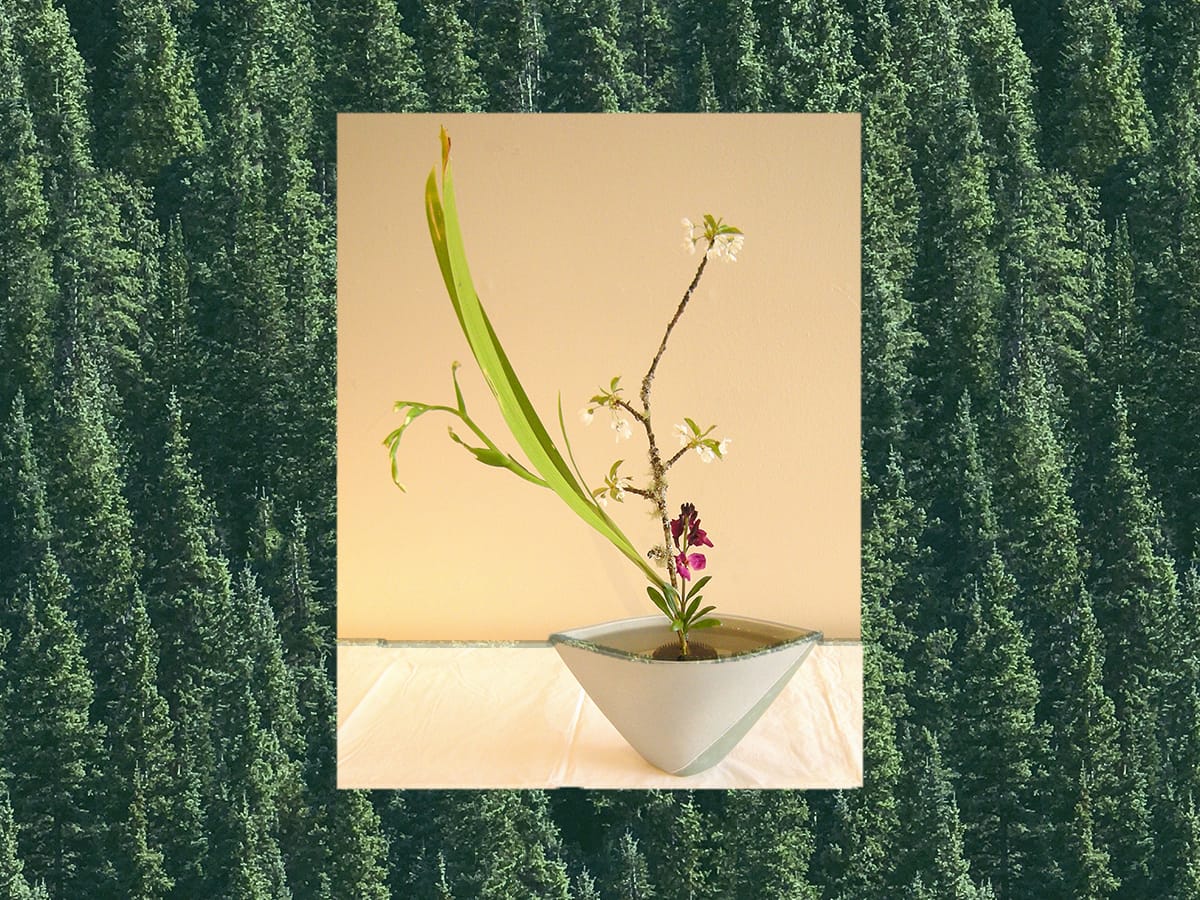

The kind of nature most appreciated in Japan is ‘cooked’ nature, as exemplified in traditional aesthetic disciplines such as bonsai and ikebana. Even after they’ve been appropriated to become bonsai or ikebana, trees and flowers are still considered parts of nature, but they need people to bring out their inherent ‘simplicity’, ‘crookedness’ and ‘austerity.’

The love of ‘cooked’ nature is bound up with the Edo period (1603-1868), when feudal lords recreated scenic spots from their home provinces in the gardens of their Tokyo mansions. These gardens had more than sentimental value. They were microcosms of how their owners understood the world. By creating a miniature world, they transformed ‘wild’ nature into an idealised shape and a symbol of another place.

Uniform, dark and overbearing – a Japanese cedar forest. | © Pakutaso

Unfortunately, this left ‘raw’ or ‘wild’ nature rather out of a job. In Japan, perceptions of the natural world are still often marked by a general sense that it is useless until fiddled with by busy human fingers.

Westerners are still in thrall to the Romantic conception of ‘raw’ nature’ as a refuge from the vanity and delusions of human society and font of all that is pure and good in the world. By contrast, many Japanese still see the natural world as essentially empty. To call a place a ‘wilderness’ is not a compliment in Japan.

In Japan, the urge to improve upon the natural world, to corral it for human ends, is so ingrained in the national psyche that it has become a fetish. Of Japan’s 30,000 rivers and streams, all but three have been dammed, and even these have had their banks and beds encased in concrete. Thirty per cent of the island nation's coastline is lined with concrete blocks 1. There is no reasonable justification for this tidy mindedness, but ever since Japan’s bubble economy popped back in the early ‘90s, pouring concrete has become akin to a nervous habit.

Gpwitteveen, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the minds of many fretful bureaucrats and vote-hungry politicians, ‘raw’ nature is just an accident waiting to happen. That’s why even the wildest parts of the country have been brought to heel, as part of the authorities’ all-consuming desire to discipline the unruly, be they bored children, disgruntled workers or the rogue branches of wayward trees.

Pity the trees of Japan! A generation ago, the government encouraged owners of mountain land to cut down the native forest for timber, and replace it with uniform ranks of sugi (杉 Japanese cedar). As a result of this mania for monoculture, every spring these cedar clones spew vast clouds of pollen into the air, sending the entire country into fits of sneezing. No wonder most Japanese slam the window shut and turn on the aircon at the first sign of spring!

Living in Tokyo, the natural world – raw, dirty and potentially dangerous - is a distant threat and easily forgotten. There aren’t many parks, and you can spend days on end without seeing a wild plant or animal. ‘Connecting with nature’ often just means recycling your PET bottles.

No, despite their much-vaunted affinity for the natural world, many Japanese people have little regard for the environment. Instead, they obsess about rituals to mark the changing seasons, and have the peculiar satisfaction of seeing their foibles recreated in the little theatres they call their gardens.

__________

Notes:

1. Lost Japan, Alex Kerr, Lonely Planet Journeys 1996, p.49