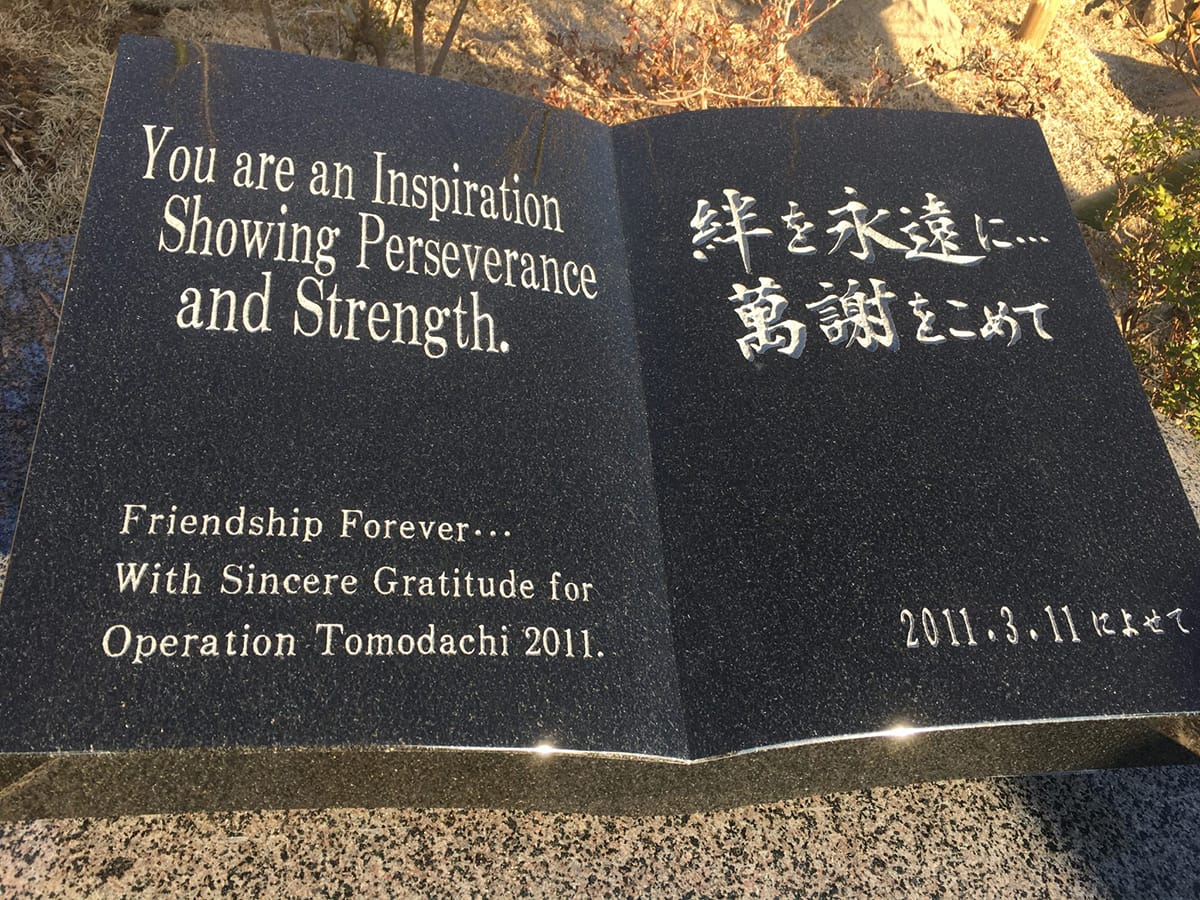

Source: The town of Oshima's way of honoring the 10th anniversary of the Great North East Japan Earthquake and tsunami was to thank those who helped them recover and rebuild. Credit: Robert D. Eldridge. | © JAPAN Forward

[3.11 Earthquake: Rebuilding] OshimaーTen Years of Friendship, Ten Years of Gratitude

- Tags:

- 3.11 / dogwood / Earthquake / Hanamizuki / Kesenuma / Oshima / post-3.11 reconstruction / Tsunami

Related Article

-

Japanese cat gets scared by earthquake, then suddenly blames owner in hilarious photo set

-

Artists Turn Kumamon Into Symbol Of Support and Solidarity In Wake Of Kumamoto Earthquakes

-

Lesson We Must Learn From The Great Tohoku Earthquake

-

“Wiped Off The Map” 5 Years Ago, The City Of Rikuzentakata Still Stands Strong

-

Not Knowing What To Do In An Earthquake, This Hamster Did The Adorable!

-

NHK Announcer Goes Off Script to Offer Comfort after Earthquake

Oshima residents are taught: “If you feel an earthquake, immediately get to high ground and do not go back for anything or delay for any reason.” It is a rule that saves lives.

Robert D. Eldridge, PhD, for JAPAN Forward

Earthquakes are scary, and tsunami are outright terrifying.

Imagine, then, being a resident of an island of more than 3,000 people located at the entrance of a bay taking the full brunt of an oncoming tsunami. And not only that, but having that tsunami divide the island in two, and repeatedly being bashed by the forward and retreating action of multiple tsunami afterwards.

This was the fate of Oshima in Kesennuma City, Miyagi Prefecture, on that tragic afternoon of March 11, 2011. Indeed, the island has long been vulnerable to such natural disasters in its history.

Aftermath of March 11, 2011. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps | © JAPAN Forward

The first recorded one dates from May 869, when approximately 1,000 people died. Ōshima was reportedly divided into three parts at that time by the tsunami that struck. The next known event was in 1585, but the number of deaths is uncertain. Less than thirty years later, a tsunami in 1611 killed approximately 500 people from Oshima. That one, four hundred years ago, appears to be the last major tsunami that caused a large loss of life.

Perhaps as a result of sharing and passing down lessons learned—namely, “if you feel an earthquake, immediately get to high ground and do not go back for anything or delay for any reason”—the number of deaths on Oshima was surprisingly low for the violence the island experienced a decade ago.

The lessons were in part communicated through several historic monuments and memorials around the island, telling of past experiences or warning not to build below a certain elevation. These warnings were for the most part honored, and as a result “only” three dozen lives were lost in the 2011 Earthquake and tsunami on Oshima.

On the 10th anniversary of the disaster this week, a new monument was dedicated on the island. This time, it was a message of hope and friendship.

Islanders organized the Hanamizuki (Dogwood) Project to build a monument thanking the United States, and especially, the U.S. Marine Corps, for its support after the Great East Japan Earthquake.

The Dogwood is a tree native to North America, and not only represents the United States, but is symbolic of the efforts by that country in 2012 to donate Dogwood trees to Japan in response to the latter’s donation of 3,000 cherry trees (sakura) to America in 1912.

Similarly, the effort by the islanders to build and dedicate a monument was self-described as a “Operation Arigato (thank you),” in response to the U.S. military’s efforts after the March 11 disaster known as “Operation Tomodachi (Friendship).”

Appropriately, the epithet on the moment stated, “Friendship Forever With Sincere Gratitude for Operation Tomodachi 2011.”

(...)

Written by Japan ForwardThe continuation of this article can be read on the "Japan Forward" site.

[3.11 Earthquake: Rebuilding] OshimaーTen Years of Friendship, Ten Years of Gratitude