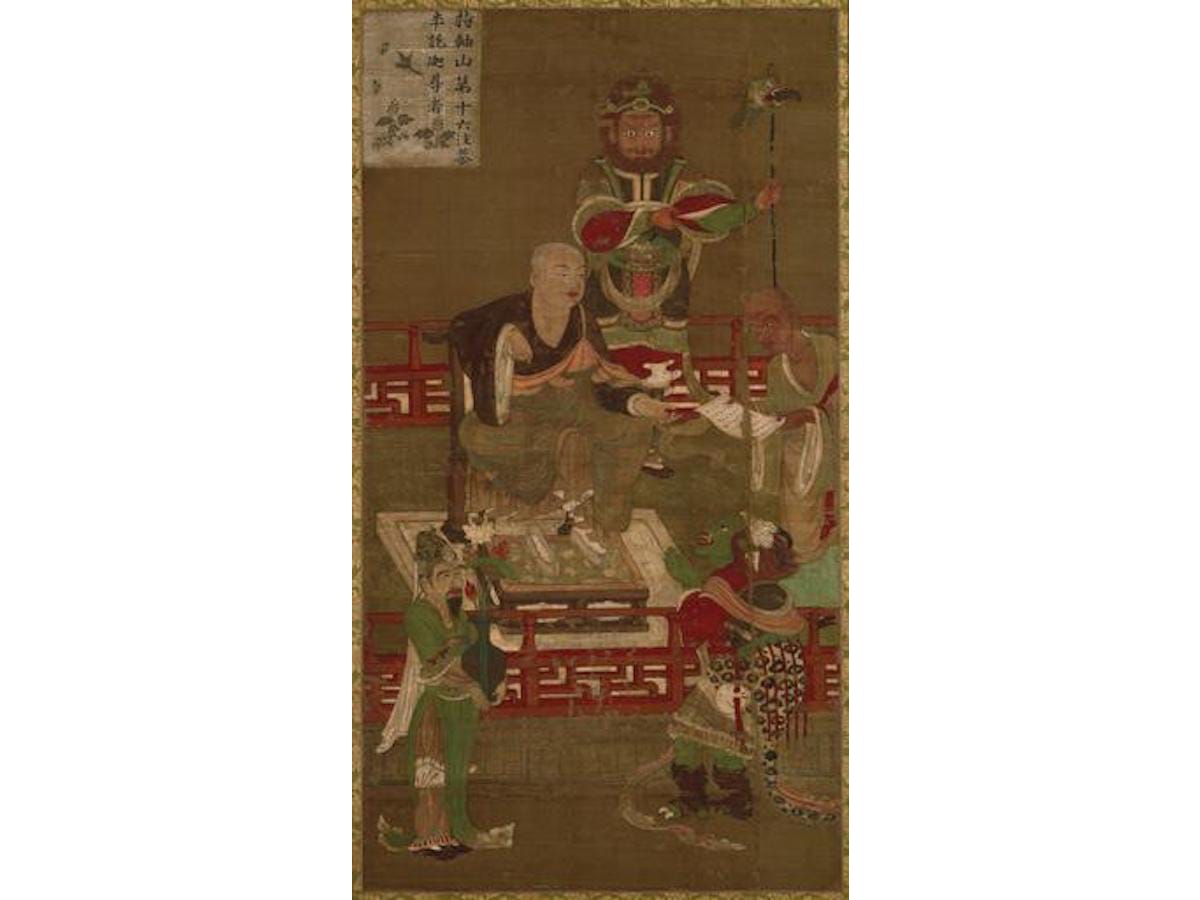

Source: © Snappygoat.com | A portrait of the ‘Dog Shogun’, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

A pioneering pet lover: the “Dog Shogun,” Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

- Tags:

- Dogs / Japanese history / Shogun / Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

Related Article

-

Shiba inu’s “double sitting” pose is just too obedient

-

Puppy Trying Watermelon For The First Time Has Delicious Revelation

-

Fluffy Ball Of Cuteness Pomeranian Puppy Just Won’t Let Go

-

Impossibly happy shiba inu’s dash up and down a canal is too funny

-

Dog Desperately Trying To Force Stick Through Door Is All Of Us

-

Japanese Shichi Go San Ceremony for Children Can Now be Performed for Pets Too

Japan’s cats and dogs are a secretive bunch. Although you wouldn’t know it from walking the streets of Tokyo, for the majority of owners like to keep their pets indoors, the country is chock-a-block with cats and dogs.

Such is the nation’s love of pets, and its reluctance to have children, that Japan is the only country in the world in which cats and dogs outnumber children. The cat and dog population first surpassed the number of children in 2003. By 2009, there were over 23 million pets in Japan, yet only 17 million children under the age of 16.

This is quite a turnaround, for until quite recently, pet ownership was considered a foreign novelty in Japan. City dwellers rarely kept pets and while there were undoubtedly more pets in the countryside, dogs were only kept for hunting, and weren’t considered pets at all.

That’s not to say that pre-modern Japan was entirely without pet lovers. The most famous of them is probably ‘the Dog Shogun,’ Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, who ruled Japan from 1680 to 1709. He became renowned for his love of dogs after he issued a string of decrees mandating the feeding and respectful burial of the hordes of stray dogs that roamed Edo, as Tokyo was then called.

An Edo-era figurine of a dog in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. | © picryl.com

Like many modern Japanese, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s love of dogs stemmed from his longing for children. At his wits end at not being able to produce a male heir, the shogun consulted his priests. They told him that his misfortune was down to the cruelty he had shown to animals in a past life. If he wanted a son, he would have to make up for his past misdeeds by taking special care of all living creatures – and especially dogs, for the zodiac animal of his birth-year was the dog.

There was a huge population of stray dogs in old Edo, mainly because the city’s samurai warriors used to breed dogs in order to use them for sword practice. Over time, they proliferated to such an extent that they became unmanageable. The samurai blithely turned them loose on to the city streets and before long Edo was overrun with packs of ferocious strays.

Previous shoguns might have sent out archers, or laid poison for the strays, but Tsunayoshi was determined to do penance for his past misdeeds and do right by the city’s burgeoning dog population. He issued a series of laws governing animal welfare, collectively called the Orders on Compassion for Living Things.

Tsunayoshi invested huge sums of money in looking after the stray dogs of the city, ordering that five huge kennels be built to house them. These kennels were reported to cover 93 hectares and to house 100,000 dogs (some records suggest there may have been as many as 200,000).

Such was the scale of the undertaking that the kennels’ annual feed bill came to US$170m in today’s money (of course, this is a pittance compared to what the dog lovers of today spend on their pets, but then the shogun wasn’t feeding them with ‘choice morsels’ or ‘luxury treats’).

Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s remains are interred at Kaneiji temple in Ueno, Tokyo. | KENPEI, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The shogun’s Orders on Compassion for Living Things didn’t only cover dogs. They also limited the weight of the loads that a working horse could be expected to carry and banned the sale of singing insects. These forerunners of animal welfare legislation were incredibly enlightened by the standards of the day and without parallel in world history at the time.

Tsunayoshi’s compassion for living things was matched by harsh punishments for anyone who mistreated animals. For example, when ten men of samurai-rank, including a constable of Osaka, were found to have been killing birds with firearms and selling them, Tsunayoshi ordered them to commit suicide by hara-kiri (ritual disembowelment).

A hanging scroll depicting an Edo-era courtesan and her attendant playing with a dog, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. | © picryl.com

While Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s laws were unprecedented, the shogun was not alone in venerating dogs. There was a ‘pet boom’ of sorts during the Edo era (1603-1868) and ukiyo-e woodblock prints of the time show dogs and cats being fussed over by prostitutes in the Yoshiwara, the licensed pleasure quarters of old Edo.

Far and away the most popular pets, however, were singing insects, such as long-horned grasshoppers. They were easier to keep than dogs, for their cages took up little space and they asked for little more than a weekly slice of cucumber. They also delighted their owners with their songs (which is more than the dog owners of today can say for their mollycoddled pets).