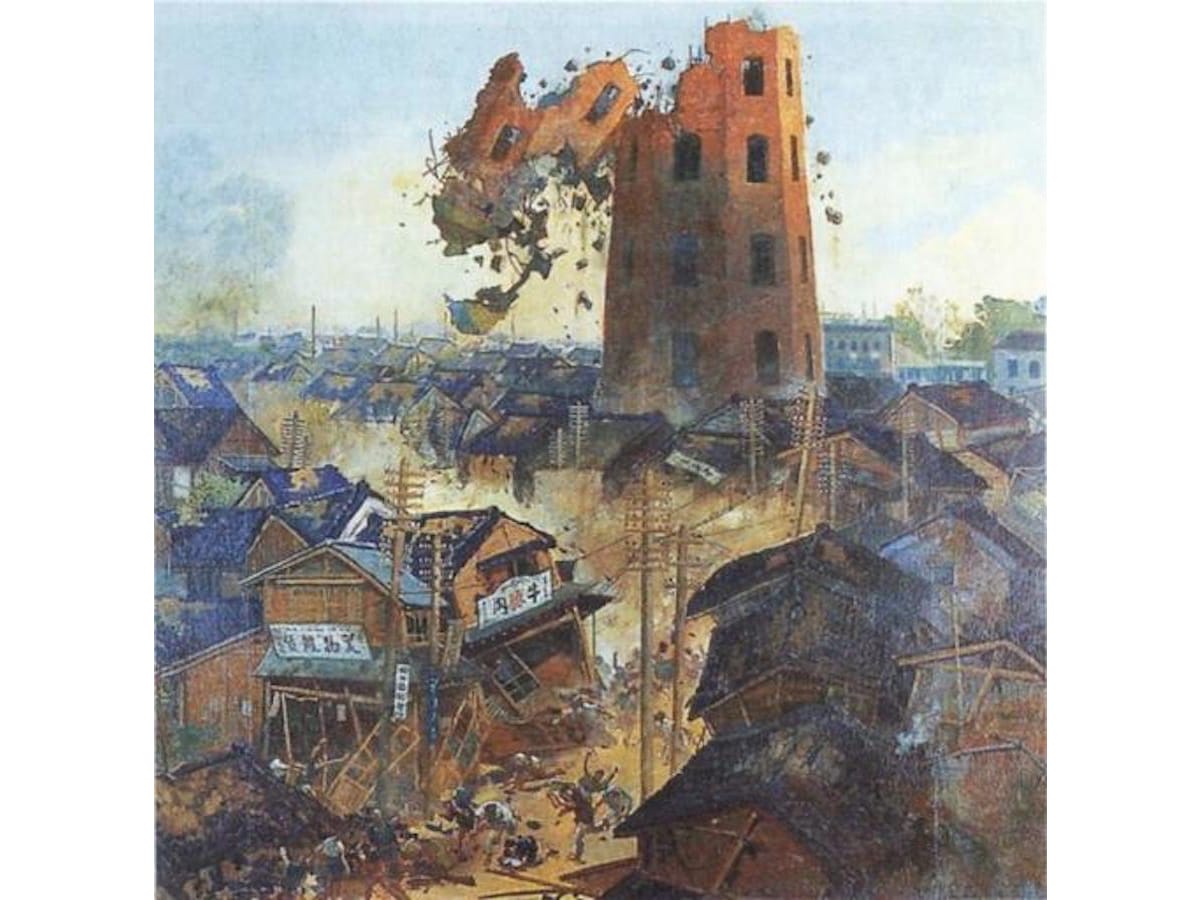

Source: 徳永柳洲 (1871-1936), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons | Artist’s impression of the collapse of the Asakusa Tower during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

Remembering the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923

- Tags:

- city planning / Fire / Great Kanto Earthquake / Japanese history / Junichiro Tanizaki / reconstruction / Tokyo / Yasunari Kawabata

Related Article

-

Three Greatest Delicacies Of The World Join Forces To Create Luxurious Savory Parfait

-

The Newest Tokyo Mascot Is Loyal Dog Hachiko’s Swirly Pink Poop

-

A pioneering pet lover: the “Dog Shogun,” Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

-

Dine In The Presence Of Zombies And Lots Of Blood At Tokyo’s Bone-Chilling Vampire Cafe

-

Tokyo Ghost Hunting: Visiting Oiwa’s Haunted Shrine in Yotsuya

-

We Visited The Cowboy Bebop Cafe in Akihabara And It Was Amazing!

Much is made of Tokyo’s ability to blend the old with the new, as if a conscious choice had been made as to what to preserve and what to demolish. In fact, the modern city is a result of a series of disasters, foremost among them the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

With the centenary fast approaching, now is a good time to remember the transformative effect the quake had on Tokyo. It killed 140,000 people and flattened most of the Low City. The damage was compounded by the Great Fire that followed the quake, for much of the city was made of wood and most people cooked over open fires. Such was the speed with which fire engulfed the city, the central fire department was reduced to ashes before firefighters had a chance to respond.

The earthquake and Great Fire destroyed most of what had survived of old Edo, including the vast Yoshiwara pleasure quarters north of Asakusa, where hundreds of working women and their customers were incinerated.

The novelist Yasunari Kawabata described walking in the aftermath of the fire: “The reader should imagine tens and hundreds of men and women as if boiled in a cauldron of mud. Muddy red cloth was strewn all up and down the banks, for most of the corpses were those of courtesans.”

Shinbashi station after the earthquake. | Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A week after the earthquake, the Taisho emperor issued an imperial rescript in response to the disaster. He said that while Japan had seen much progress “in science and human wisdom,” this had been accompanied by “frivolous and extravagant habits.” His words were taken as a suggestion that the quake had been divine retribution for sinful behaviour.

Not everyone thought so. When the writer and theatre producer Tsubouchi Shoyo heard a member of the Diet say that the disaster was divine retribution for the looseness and frivolity of the city’s people, he asked him why, that being the case, God should have chosen to punish the hundreds of thousands of people who lived east of the river, most of whom didn’t have enough money to be loose or frivolous.

Reconstruction of Tokyo began before the last embers were out. People were proud of the speed with which they went about rebuilding the ruined city. Common mercantile wisdom held that if a shop had not resumed business within three days, it had no future.

The Reconstruction Song became popular. “Completely burned out. But see/ The son of Edo has not lost his spirit/ So soon, these rows and rows of barracks/ And we can view the moon from our beds.”

Aerial view of Nihonbashi after the quake; note the burned-out wooden bridge to the north. | English: Imperial Japanese Army日本語: 日本陸軍, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Before the earthquake, Tokyo had still been much like old Edo: a city of canals and barges, of evenings spent on the water watching the fireflies and being entertained by geisha.

But the fires that swept through the city turned its waterways into death traps. There were only five bridges across the Sumida River, and they all had wooden floors, which caught fire. It seems likely that more people drowned than died in the quake or the fires. After the disaster, four hundred new bridges were built and many of the city’s canals were filled in with rubble.

Fifty small parks were also laid out. Motomachi Park, which opened near Ochanomizu in 1930, is one of the few to have survived in its original form. Three big new parks were also laid out in the Low City, Sumida Park and Hamachō Park being two of them.

Yasunari Kawabata describes meeting a friend who had just come back from the new Sumida Park. He raved about the wonderful views of Mt. Tsukuba, and how, once the cherry trees had matured, it would surely be a rival to the world’s great riverside parks.

Temporary housing built in the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine after the earthquake. | Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

City planners also laid out many wide new streets to ease overcrowding and act as firebreaks. Among them was Showa-dōri, which runs from Ueno down to Ginza and Shimbashi. Some compared the new street to the Champs-Elysees in Paris, but Kawabata was not impressed. “I saw the pains of Tokyo. I could, if I must, see a brave new departure, but mostly I saw the rawness of the wounds, the weariness, the grim, empty appearance of health.”

Kawabata asked a friend if it was no longer possible to put up a Japanese style building. “But all these American things are Tokyo itself,” his friend replied. “They may look peculiar now, but we’ll be used to them in ten years or so. They may even turn out to be beautiful.”

Showa-dōri as it looks today. | G-item, © PIXTA

Kawabata may have been nostalgic for old Edo, but many Japanese were glad to leave the old city behind. The writer Junichiro Tanizaki looked forward to living in a truly modern city. “I was one of those who uttered cries of delight at the grand visions of the home minister, Goto Shimpei. Three billion yen would go into buying up the whole of the burned wastes and making them over into something regular and orderly.”

Tokyo was rebuilt as a modern city, one in which a recognisably modern culture flourished. As the American writer John Dower put it, being in Tokyo in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, one had “a real sense of being part of the world.”

But Tanizaki felt disappointed by the new city. “The recovery in ten years, though remarkable, has not been the transformation I looked for. The old tangle of Tokyo streets is still very much with us… The truth is that my imagination got ahead of me. Westernization has not been as I foresaw.”

The area north of Sumida Park today. | © pixabay.com

The firebombing of Tokyo in 1945 gave the city authorities a second chance to undo “the old tangle of Tokyo streets.” In rebuilding the city after the war, the authorities made a priority of appearing modern, just as they had after the Great Kanto Earthquake.

Some beauty would have been nice too, but it was very much a secondary concern. That’s why today, Mt. Tsukuba can no longer be seen from Sumida Park, and neither can the River Sumida, for it has been lined with high walls to stop it from flooding.

With most of the old canals filled in, Tokyo is no longer a watery city. The most extensive part of the present city in which something like the mood of the old Low City can still be sensed is Yanaka, which was spared the fires that followed the earthquake of 1923.

What we’re left with is the “grim, empty appearance of health” that Yasunari Kawabata described after walking in the new Low City. In modern-day Tokyo, health, happiness and brightness, both physical and mental, have become the civic virtues on which the city styles itself.