Source: The red gate and colourful neon street signs at the Shinjuku-dori entrance to Kabukichō. | Basile Morin, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A potted history of Kabukichō, nightlife capital of Tokyo

- Tags:

- Japanese history / Kabukicho / Tokyo / urban planning

Related Article

-

Attempting The Monster Ramen Challenge In Akihabara, Tokyo!

-

Café Benisica, Birthplace of Japanese Pizza Toast, Lets You Savor the Showa Era in Yurakucho

-

Brush Up On Your Manga History At The Upcoming “Journey Of Manga” Art Exhibition

-

New Tokyo Taxi Service Offers Free Rides And Free Noodles [Hands-On Report]

-

Stay cool this summer with this citrus infused menu from GODIVA café Tokyo

-

Hanayashiki: A Trip To Japan’s Oldest Amusement Park

Kabukichō is a visual fest. It must have more neon than any other Tokyo neighbourhood, which is no small boast in the most neon-saturated city in the world. At weekends, the excitement is palpable.

Yet it's hard to find reminders of the past here. That's because, in common with much of Shinjuku, most of Kabukichō was levelled during WW2. After the war, the government introduced a Special City Planning Act, whereby it made ambitious plans to revive business in the capital, and that included the night-time economy.

But the government also supported initiatives by local bigwigs. In this part of Shinjuku, that meant the ambitious scheme envisaged by entrepreneur Kihei Suzuki 鈴木喜兵衛 and Mohei Mineshima 峯島茂兵, who was the biggest landlord in Kabukichō.

This was quite a turnaround, for Kabukichō was not particularly known for its nightlife before the war. It wasn't even called Kabukichō, but Tsunohazu 角筈. Suzuki wanted to turn the neighbourhood into a major entertainment district and to get the ball rolling, he wanted the Kabuki Theatre Corporation to relocate to Shinjuku - so keenly that in 1948 he had the area renamed Kabukicho by way of welcome.

A view of the new Hotel Gracery and the iconic figure of Godzilla. | © pxfuel.com

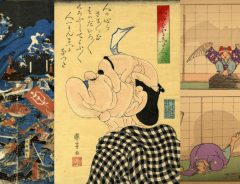

In the end, the Kabuki Theatre Corporation chose not to relocate, but the name stuck. It is fitting for other reasons. The verb kabuku 傾く isn't used much these days, but one of its meanings is 'to dress flashily.' It was first used to describe the dashing young blades of the Edo period, who became known as kabukimono かぶき者. They even had their own dance - kabuki odori かぶき踊り- which is the origin of the theatrical art form known as kabuki.

Despite this early setback, Kihei Suzuki succeeded in enticing many of Tokyo's theatre, cinema and dancehall owners to relocate to Kabukichō from rival nightspots like Asakusa and Ginza. In 1956, the Tokyu Bunka Kaikan 東急文化会館 was completed. Sitting alongside the Milano-za ミラノ座, Japan's biggest cinema, the Shinjuku Koma Theatre 新宿コマ劇場 and the Tokyo Skate Rink, it made Kabukichō the hottest nightlife hotspot in the city.

By the time poor Kihei Suzuki died in 1967, he had been driven into bankruptcy by the redevelopment process, but his dream of creating 'a moral business district' in Shinjuku had been realised.

There was, however, always another, not quite so moral side to Kabukichō. Golden Gai ゴールデン街, the warren of tiny bars on the eastern edge of the neighbourhood, was created by the people who moved in the area after the black market in front of Shinjuku station was shut down in the '50s. It was known as 'the blue line' and had many eateries that doubled as brothels.

The warren of bars known as Golden Gai as seen from above. | てらたにこういち, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

After the Anti-Prostitution Act came into effect in 1958, the eateries became drinking establishments, and that's when the block started to be called Golden Gai. Journalists and intellectual types loved it, and it was only their protection that saved it from the wrecking ball that swept away most remnants of the Showa era in Tokyo in the post-war years.

The authorities have long wanted to 're-develop' Golden Gai in order to attract more tourists, so it is ironic that the neighbourhood has only been saved from demolition by foreign tourists. Mass tourism has become a mainstay of the Japanese economy over the past two decades, and Golden Gai has become one of the must-see sights on the Tokyo tourist trail. This has come as a surprise to some tourism bosses, who can't understand the inimitably seedy appeal of this remnant of post-war Tokyo.

But the ward authorities let Golden Gai be and pressed ahead with the frying of bigger fish. Several large hotels have sprung up in Kabukichō to capitalise on what was, until coronavirus came along, a boom in the number of foreign tourists visiting Japan.

One is the Hotel Gracery Shinjuku, which stands on the site of the old Milano-za cinema, which closed in 2014. Another is the Shinjuku Tokyu Milano, which is scheduled to open in 2022. Once complete, the 48-story hotel will be far and away the tallest building in the neighbourhood, coming in at 225m.