Source: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b9/Denny_Tamaki_and_Shinz%C5%8D_Abe.jpg

Okinawan Governor Seeks to Back Anti-hate Laws with Criminal Punishments

- Tags:

- anti-hate law / hate speech / Okinawa

Related Article

-

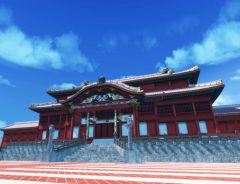

As Shuri Castle undergoes reconstruction, a virtual version debuts on Virtual OKINAWA

-

Phoenix-Like Clouds Illuminate The Skies of Okinawa Before Daybreak

-

All of Japan’s Traditional Festivals and Regional Delicacies Under One Roof: Furusato Matsuri at Tokyo Dome

-

Peer into the Okinawan seas with these breathtakingly beautiful Japanese glasses

-

Renowned photographer Xavier Tera takes us to Okinawa with his new photo book & exhibition

-

Dive shop shows the ominous beauty of the Demon King’s Palace in Okinawa

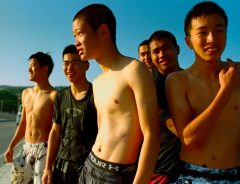

Japanese citizens are by and large peace-loving and tolerant. The vast majority obey the law, protect group consensus, and avoid rocking the boat. Nevertheless, in this largely homogenous society—approximately 98% of the country’s residents are Japanese—there are significant struggles experienced by social minorities.

According to a 2017 survey conducted by the Ministry of Justice, a third of foreign residents reported they had experienced inflammatory remarks owing to their ethnicity. While most comments reportedly came from strangers, often, the perpetrator was a business acquaintance such as a boss or coworker. Furthermore, 40% of respondents claimed they had experienced housing discrimination.

Over the last several years, organizations and residents have begun to push back on these disturbing findings. Government officials have pledged to educate the public on human rights issues, while large employers like Rakuten have openly embraced diversity platforms. Recently, Okinawan mayor Denny Tamaki, who is half American and half Japanese, is pledging to make anti-hate legislation even more powerful throughout the island prefecture.

Japan’s Anti-Hate Laws

Through the early-to-mid 2010s, tensions between Japan and Korea flared following the development of issues surrounding the historical detainment of comfort women, sex slaves, in Japan during WWII. During the period, gatherings of exacerbated ultra-right-wing groups in Japan increased. Labeled hate speech rallies, many called for the removal, or even execution, of Korean residents in Japan.

In Japan, The Hate Speech Act of 2016 is the law dealing with hate speech ratified in reaction to the treatment of Koreans during this period. Although the law was passed in order to comply with the United Nations “International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination,” many view the legislation as toothless.

Critics are likely right. The law is narrowly aimed at speech involving physical threats against a minority resident. Nevertheless, no penalties are defined by the law, and racialized insults are not part of its purview. As such, in online arenas, in particular, hate speech is commonly experienced by ethnic minorities.

Okinawan Decision

At a press conference in Naha city hall in May 2020, Okinawan governor Denny Tamaki announced a review of the island prefecture’s anti-hate ordinance. According to Tamaki, “Hate speech should not be allowed. It is necessary to study how to restrict [the behavior] and apply penalties.”

Okinawa isn’t the first prefecture to strengthen anti-hate laws. Last year, Kawasaki introduced legislation adding punitive measures against perpetrators who repeatedly harass residents. The ordinance includes a fine of up to 500,000 JPY ($4,600) and is aimed at remarks such as "Get out of Japan," "You should die," "You are a cockroach," and the like in public places, using loudspeakers, banners, and so forth. The law is set to come into effect July 2020.

Tamaki plans to leverage the Kawasaki precedent as well as others throughout the country. He explained, "It is also necessary for the administration to thoroughly examine and study precedents in other prefectures.

Denny Tamaki

Although this stance is not common among governors in Japan, Denny Tamaki is no stranger to confrontation. The opposition lawmaker originally won the gubernatorial election based on his strong anti-U.S. military agenda.

Okinawa hosts some 54,000 American troops who often find themselves at odds with locals. As residents' frustrations have grown in recent history, calls to act have increased after numerous safety breaches occurred. Tamaki rode to victory by vowing to obstruct the relocation of the Futenma airbase to the remote northern Henoko district. Rather, the governor aligned himself with the public sentiment calling for the base to be removed entirely from Okinawa. Tamaki has been lobbying the central government to suggest the base be moved to Guam or Australia instead.

While the future of the airbase remains in question, it seems that local sentiment is unlikely to change anytime soon. Nevertheless, new measures against hate speech place restraints on the public expression of any ill-will that the controversial arrangement may garnish. Perhaps Tamaki's mixed background, if only figuratively, is helping him walk a fine line as he navigates the current issue of the Futenma airbase.