- Tags:

- coronavirus / COVID-19 / Obon

Related Article

-

Kid Dressed Like This on First Day Back to School During Pandemic

-

Hokkaido zoo and manga artists team up to protect animals during pandemic

-

Security guard and cat locked in standoff have touching reunion after museum reopens

-

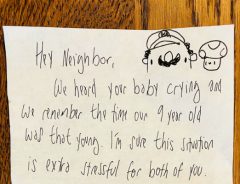

Dad gets note from neighbor about crying baby, fears worst, receives heartwarming gesture during cornavirus stress

-

Indian village disco takes over Shibuya for New Year’s Eve 2020

-

Claustrophobic haunted toilet and caskets introduced in Japan for socially distanced scares

Florentyna Leow, JAPAN Forward

Every year on the 14th of August, the Matsuyama family loads up their car with 10 lanterns in preparation for the yearly Obon rituals on the tiny island of Fukuejima, located some 100 km off the coast of Nagasaki prefecture.

Summer days are long on the Goto Islands, and it’s still bright when they set out at 5 in the evening. It is also hot enough to warrant hats and umbrellas for some shade. Though their family grave is within walking distance, the lanterns are large and heavy, and few living in the countryside choose to walk when they can drive.

On this evening, the normally quiet graveyard near the Matsuyamas’ house in Tomie town takes on a festive air. Those who left for cities on the mainland have returned for the annual ancestral rituals, and it’s not unusual to run into old classmates among the graves.

Candles are lit. Slowly, the graveyard transforms into a sea of lanterns glimmering in the fading twilight. Children in colorful yukata play with fireworks and light firecrackers, while the adults lounge and talk, fanning themselves with uchiwa.

Firecrackers at Obon might seem sacrilegious to those outside of Nagasaki. But for the people of the Goto Islands, the exuberant pops and bangs are just their way of celebrating Obon with the ancestral spirits.

At least, this is how Tokyo resident Akiko Matsuyama remembers celebrating Obon growing up. But like many others in urban Japan, she won’t be returning to the countryside this summer––not while the spectre of COVID-19 continues to loom large.

‘Don’t Come Home’ Prevails This Year

Obon is one of Japan’s three major holidays seasons, and is usually when many Japanese people return to their hometowns to pay their respects at the ancestral graves. While the festival itself officially lasts from August 13-15, the days leading to and after the festival typically see congested roads and trains, marking one of Japan’s peak travel seasons.

This year there is a significant drop in traffic. According to a survey carried out by incense company Nippon Kodo in early July, 34.2% out of 1036 respondents had definitively decided not to return to their hometowns, with another 28.6% remaining undecided. The results of a different survey targeting residents of Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa prefectures carried out by Cross Marketing Inc. were even more drastic: 78.2% of 1,100 surveyed said they had no plans to go home for Obon.

The data bears out at the informal level as well. A search of Twitter posts around the topic, for instance, revealed an overwhelming majority of users apparently refraining from returning to their hometowns for the holiday this year.

“I usually go home during Obon,” said Kirara Yamashita, who hails from the riverside town of Gujo in Gifu prefecture, and is presently a 3rd-year student at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies. “But Obon itself is not quite so important, compared to the risk of spreading coronavirus.”

Yamashita’s sentiments are common among urban dwellers and rural residents alike. The risk of traveling to one’s hometown from the city lies in being a potential asymptomatic carrier of the virus, or even contracting it en route. Community transmission is highly likely at this stage of the pandemic. Japan might have expanded its overall testing capacity, but it still lags far behind most nations. Many in rural areas there is likely to be no recourse to virus tests at all without traveling to the nearest large city.

Another major concern for rural Japan is its comparatively fragile medical system. There are far fewer hospitals per capita, and overall they are under equipped for even a small uptick in cases. According to Matsuyama’s mother, Yasuko, the main hospital in Goto City on Fukuejima had only 4 beds set aside for potential coronavirus patients at the time of writing.

The elderly make up a large proportion of Japan’s rural population, and they are highly wary of potential carriers returning from major cities. Both Yamashita and Matsuyama, whose surviving grandparents are 89 and 90 respectively, have elected not to go back for this very reason. Yamashita’s parents explicitly asked her not to come home to Gujo this yearーa common refrain from many in rural Japan to their children in the cities.

Written by Japan ForwardThe continuation of this article can be read on the "Japan Forward" site.

Going Home For Obon: How COVID-19 Has Changed Everyone’s Plans