Source: © pixabay.com

Peeking behind the scenes at a hot spring inn and other everyday aspects of Japan

- Tags:

- Hot Springs / Onsen / Ryokan

Related Article

-

Vacation Like An Imperial King At The Heian Period-Themed Inn

-

Explore Zao Onsen safely at night with these social distance lanterns

-

Dogo Onsen: Wrapped in History and Charm

-

Tiny Japanese Lizards Soaking in A Paper Cup Bath Is The Cutest Thing You’ll See This Week [Video]

-

Hot Springs Town Nasushiobara’s Tasty Secret Is Out: You Can’t Keep This Under Wraps![PR]

-

Crowdfunding started to revive Minobu’s only onsen and restore local tourism

Many aspects of Japanese entertainment and culture are famous worldwide—Pokemon, Dragonball Z, and a host of other animes are universally recognized. Sushi restaurants are popular in landlocked regions of America, and Hello Kitty products are available in over 60 countries. Oh, and who can forget that 1990s craze, Tamagotchis.

Come to think of it, I haven’t fed mine in decades…His hunger meter must be off the charts.

Regardless, Japan’s soft power success is no coincidence. Despite a timid period following WWII, the country sought to export it’s culture throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Encouraged by warming ties throughout East and Southeast Asia. In 1994, broadcast laws changed, allowing anime to explode in popularity overseas. In recent years, the Ministry of Economic, Trade, and Industry has continued the cultural export initiative, particularly under the guise of its Cool Japan PR strategy.

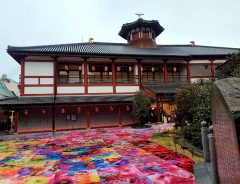

Traditional Japanese Inn and Hot Springs

Yet, the fantastical worlds of Studio Ghibli or the bleeps and bloops of high-tech gizmodgery don't necessarily paint a complete picture of Japanese life. I can attest first hand that many aspects of the culture are hidden from prying eyes abroad.

On his YouTube account, Life Where I’m From seeks to highlight more everyday but much less promoted aspects of Japanese culture. His channel covers several topics, but the top of the list was a behind the scenes glimpse of a family-owned traditional inn and hot spring.

The vlogger begins the video showing off Toshimaya Tsukihama No Yu, a hot spring inn in Ibaraki. After explaining that many Japanese families travel to such hotels for weekend getaways, the staff relates the history of the resort to the vlogger. The family-owned business has a long history and has been passed down for generations. It became a hot spring in 1931 but operated as a tobacco shop, a convenience, and various other entities before that.

More importantly, however, Life Where I'm From takes a few moments to explain hot spring culture in Japan. While it may seem like a pain to travel several hours for a bath, guests come for an all-encompassing experience. Hot spring inns are usually beautifully constructed buildings in scenic getaways. They provide a chance to slow down, enjoy the outdoors, eat a fantastic meal, and, of course, enjoy a relaxing soak. Nevertheless, as the video shows, there is a lot of consideration and work involved in creating a noteworthy destination for visitors.

Making Ainu Cloth from Tree Bark

The Ainu are Japanese indigenous people native to the northern island of Hokkaido. Although there culture was practically wiped out over the last century, there has been considerable effort to revitalize their heritage in recent years.

As part of this initiative, Life Where I’m From followed a group of Ainu natives as they wandered deep into a Hokkaido forest. Following custom, they went with the purpose of harvesting bark to make a versatile and traditional cloth.

If you recognize the host Maya, we covered her Ainu language lessons before. On this occasion, she is walking the vlogger through the process of making attus cloth. Maya’s whole family is needed because the process of harvesting and processing the bark takes considerable effort.

First thing’s first; the group searches for Ohyo trees from which to harvest the raw material. At this time of year, the usually cumbersome bark can be removed easily in long swathes. After stripping the trees, the inner portion is separated from the hard exterior. The whole ordeal takes a communal effort, allowing members to socialize as they teach the customs to newcomers.

Still, the raw inner bark must be further processed. It is boiled in a vat and strained in river water. Finally, it is dyed, separated, and twisted into thread. The thread is used to make many items, including garments and traditional crafts.

Urban vs Rural Lifestyles

Ninety-two percent of Japanese residents live in urban centers. While the hustle and bustle of congested metropolitan areas have their perks, there are just as many negatives. This is even more true in the days of COVID-19.

Life Where I’m From examined why Japanese cities like Tokyo have such a great draw, and whether less popular rural communities might be a better choice.

The vlogger follows Sherry, who lives just outside of moderately-populated Matsuyama city in Shikoku. Sherry was born in the area and has lived there her whole life except for a study abroad stint in America.

For Sherry, the countryside is quiet while offering several worthwhile amenities. The area she lives is not congested and a short car ride from beaches and mountains. Residents of the region are much warmer than city-dwellers, and it's easy to talk to strangers and ask for help. Also, due to the limited population, there is always parking—definitely a plus.

While the video goes on to cite other typical pros and cons of urban and rural communities, I think that the most crucial part is what the clip shows. Smaller rural areas offer a different pallet of experiences compared to the likes of Tokyo or Osaka. There are more traditional aspects to everyday life, while city centers boast a more cosmopolitan feel.