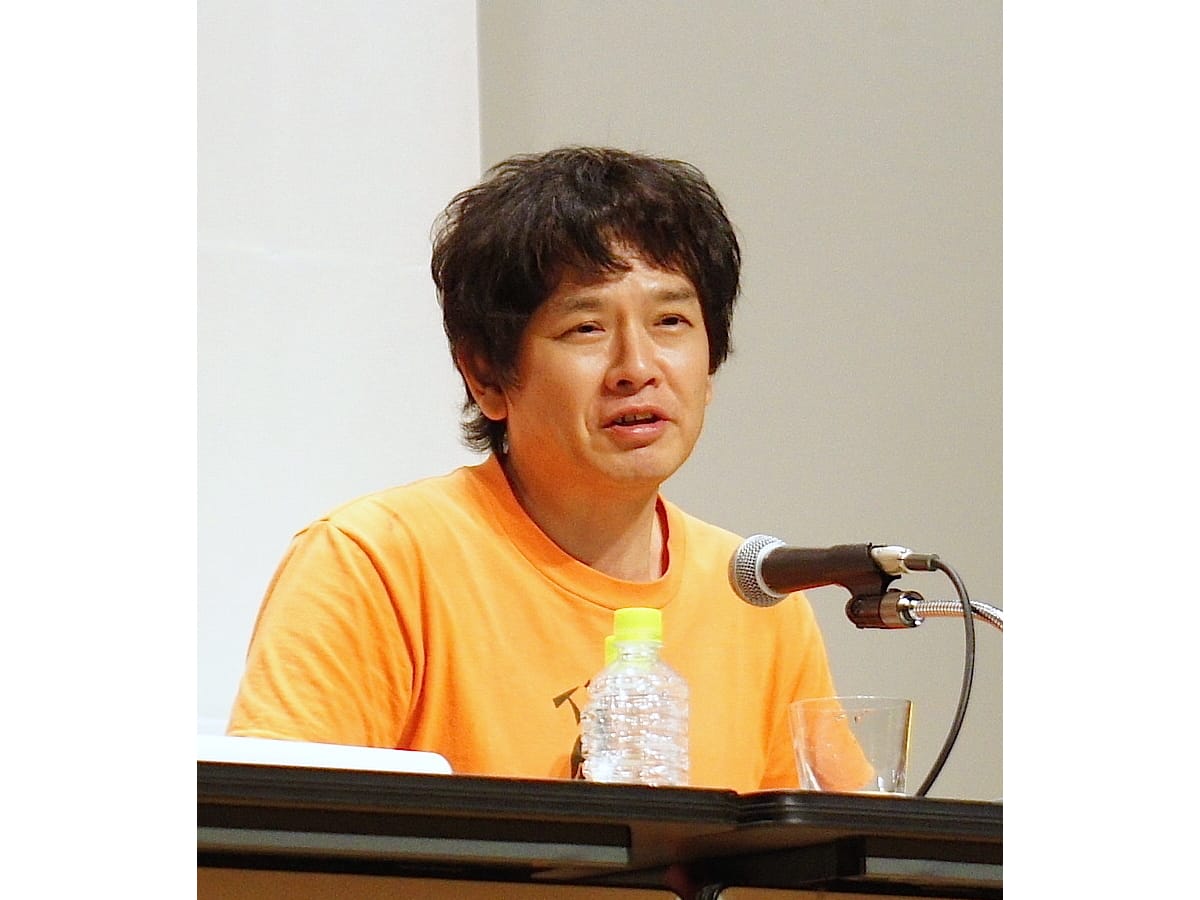

Source: Hsinhuei Chiou / CC BY-SA 4.0

Profile of Yoshitomo Nara, Japan’s most expensive living artist

- Tags:

- Artist / Children / Yoshitomo Nara

Related Article

-

How long does it take pro Japanese illustrators to use up a single pen?

-

Problem solved: these Japanese Instagrammer children know how to send a message

-

Kintsugi Artist Volunteers To Repair Ceramics Broken During Kumamoto Earthquake

-

Artist Namura Kiyu’s parody of a popular Xmas gift and her response to a Tweet reacting to it go viral

-

Take a moment and see the world through the eyes of a child with these manga

-

The Chill and Retro Pixel Art of Motocross Saito

In October 2019, the painting "Knife Behind Back" was sold by Sotheby’s auctioneers for US$25 million, making Yoshitomo Nara the most expensive living Japanese artist.

"Knife Behind Back," which the artist painted in 2000, has all the characteristics of his previous work: a malevolent child painted in comic book style. This one comes with an added hint of mystery, in that there is no knife in the picture, just a little girl with a look of grim determination on her face holding her hand behind her back.

What excites people about artists like Yoshitomo Nara is their focus on children, and the way they use art forms originally intended for children, like manga and anime, to hint at adult themes. The blurring of the boundary between adult and child, guilt and innocence, high art and popular art is a hot topic across the developed world, and nowhere more so than in Japan.

Peyri Herrera | © Flickr.com (CC by ND 2.0)

Yoshitomo Nara had a pretty typical upbringing. The youngest of three boys, he grew up in Aomori. Both of his parents worked, so he spent a lot of time at home, and like millions of kids across Japan, he spent a lot of time feeling lonely.

“I was lonely, and music and animals were a comfort,” Nara has admitted. “I could communicate better with animals, without words, than communicating verbally with humans.” It’s this loneliness and inability to communicate that gives Nara’s seemingly innocent pictures their edge of menace.

Loneliness is a constant in Nara’s work. A few years ago, he gave an interview in which he talked about how the period he spent in Berlin as an art student shaped his outlook. “In Berlin I was a foreigner and I had no language skills, so I felt very much isolated. It was like growing up in Aomori, which is very much disconnected from Japan.”

Becky Snyder | © Flickr.com (CC by SA 2.0)

Around 2001, Nara became associated with a group of Japanese artists known as Superflat, which also included Takashi Murakami and Chiho Aoshima. They used lurid colours, patterns, and characters from manga and anime to draw attention to the banality of Japan’s media-saturated, youth-obsessed, hyper-consumerist culture.

Nara became known for his pictures of young children. Seemingly innocent at first glance, a closer look reveals a darker side to these boys and girls, who brandish knives, crucifixes and flaming torches, or sport vampire fangs and smoke cigarettes.

FaceMePLS | © Flickr.com (CC by SA 2.0)

The appeal of Nara’s subjects is that they are both cute and scarey – kawaii and kowai – the two poles of young Japan’s rather emaciated emotional landscape.

Nara has said of his subjects, “I kind of see the children among other, bigger, bad people all around them, who are holding bigger knives.” His explanation hints at the contradictory nature of young Japanese. They might seem complete innocents, happy consumers with a love of fantasy and no interest in the adult world of politics, history or current affairs.

This is certainly what their parents’ generation likes to think of the world of children. It’s also convenient for powerful interest groups, because it leaves them free to do as they like. And it’s true that most young Japanese aren’t much interested in non-fiction. They take little interest in the news, documentaries or current affairs.

sprklg | © Flickr.com (CC by SA 2.0)

Instead, they express themselves through - and find themselves in – fiction. As a result, their imaginary worlds have become vast repositories of pent up feelings: of love, delight, and play, but also righteous indignation, frustration, and violence.

As long as fiction and non-fiction are clearly demarcated, stability can be maintained. But there is always the danger that this nation of kawaii dreamers will wake from their dream world and feel that they have been deceived by those who claim to be watching over them.

That’s why the hidden knife is so potent: it highlights the latent insurgent power of children and the unexpected threat posed by those considered too innocent and/or insignificant to have opinions of their own.

When Nara talks about “the happy children of Japan,” he is being ironic. Post-war Japan is built on the premise of treating people like children, who cannot be trusted with the whole, uncomfortable truth. Former Financial Times Tokyo correspondent Richard Pilling says something similar in his book, "Bending Adversity: Japan and the Art of Survival": “The happy children of Japan live in a fantasy land of happy consumerism, exquisite design, and exacting hygiene standards while the blood-and-guts business of defending their nation is outsourced to the Americans.”

Japan’s ‘happy children’ might be happy, pretty and clean, but they are no less stunted than bonsai plants. The point is that Japan’s civil society is woefully under-developed, and there’s very little popular participation in the political life of the country. Most people don’t take much interest in current affairs and this makes shopping, entertainment, manga, and anime especially important. But because they’re displacement activities, they’re always a bit unreal.