Screen capture from Instagram (tomfeiling68) - with permission

Indian village disco takes over Shibuya for New Year’s Eve 2020

- Tags:

- coronavirus / Indian / New Year's Eve / Party / Popular Sovereignty Party / protests

Related Article

-

Akita Maiko hold online dance parties for children during the COVID-19 pandemic

-

Traditional Japanese sweets maker battles coronavirus with creepy cute “cats wearing masks” dumplings

-

2021 New Year’s Osechi pre-orders begin, revealing pandemic-adapted offerings

-

Japanese maker mass produces lightweight and easy to assemble partitions for use at events

-

Domino’s Japan’s “Halloween Roulette” Pizza Spikes One Slice with Ghost Pepper Sauce

-

Japanese cheerleader bar carries on business with faceshield masks and gloves–for everyone

Thanks to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, New Year’s Eve in Tokyo was always going to be a subdued affair, even by the extraordinarily subdued standards of mass gatherings in Japan.

Even in a normal year, most Japanese are more likely to spend New Year’s Eve at home with their families, eating soba and getting a good night’s sleep before going to a local shrine or temple to give thanks for the year just gone and pray for the year to come.

“Still, there are sure to be a few revellers on the streets of Shibuya,” I said to myself.” Of course, I didn’t want to expose myself to the possibility of picking up the lurgy. If there were masses of people on the streets, I’d observe things from the side-lines for a while and call it a night.

But then I read online that the festivities at Shibuya Crossing had been cancelled. This struck me as a typically mealy-mouthed way of discouraging people from going. After all, the festivities have always been a spontaneous gathering of people looking for a good time. How can you call off an event that wasn’t organised in the first place?

Never having spent NYE in Shibuya before, I don’t know how raucous things usually get, but thanks to one too many drinks at home we missed whatever was happening there. At the stroke of midnight, as the world bid good riddance to the bad rubbish of 2020, we were still en route to Shibuya. Maybe things were kicking off further down the road, but I certainly heard no countdown or festive cheers from the bars in Yoyogi.

Coming out at Bunkamura, we saw small crowds of people in the side streets, but they all seemed to be foreigners, mostly Indian and mostly male. Where were the women? And where were the Japanese?

Photo by George Lloyd

Fortunately, things were a bit livelier outside Shibuya station. A funk band was playing in wigs and clown costumes. They were pretty good too. Around them were twenty or so of what I at first took to be their fans, but then I noticed that they were all holding banners from Kokuminshukento 国民主権党, or the Popular Sovereignty Party.

I’d never heard of them, but I’m all for some new faces in Japan’s staid political scene. Judging by their banners, however, they’re not going to be winning elections any time soon. ‘The coronavirus pandemic is a hoax’, read one of them; ‘PCR tests and vaccinations should not be made compulsory’ read another.

Photo by George Lloyd

When I asked a fan/ party member why he was protesting, he said that he was concerned that the measures the government is taking to control the spread of the virus have not been subject to democratic scrutiny. Worse, the press has done nothing to question the government’s approach to the virus, choosing instead to keep the population in a state of fear.

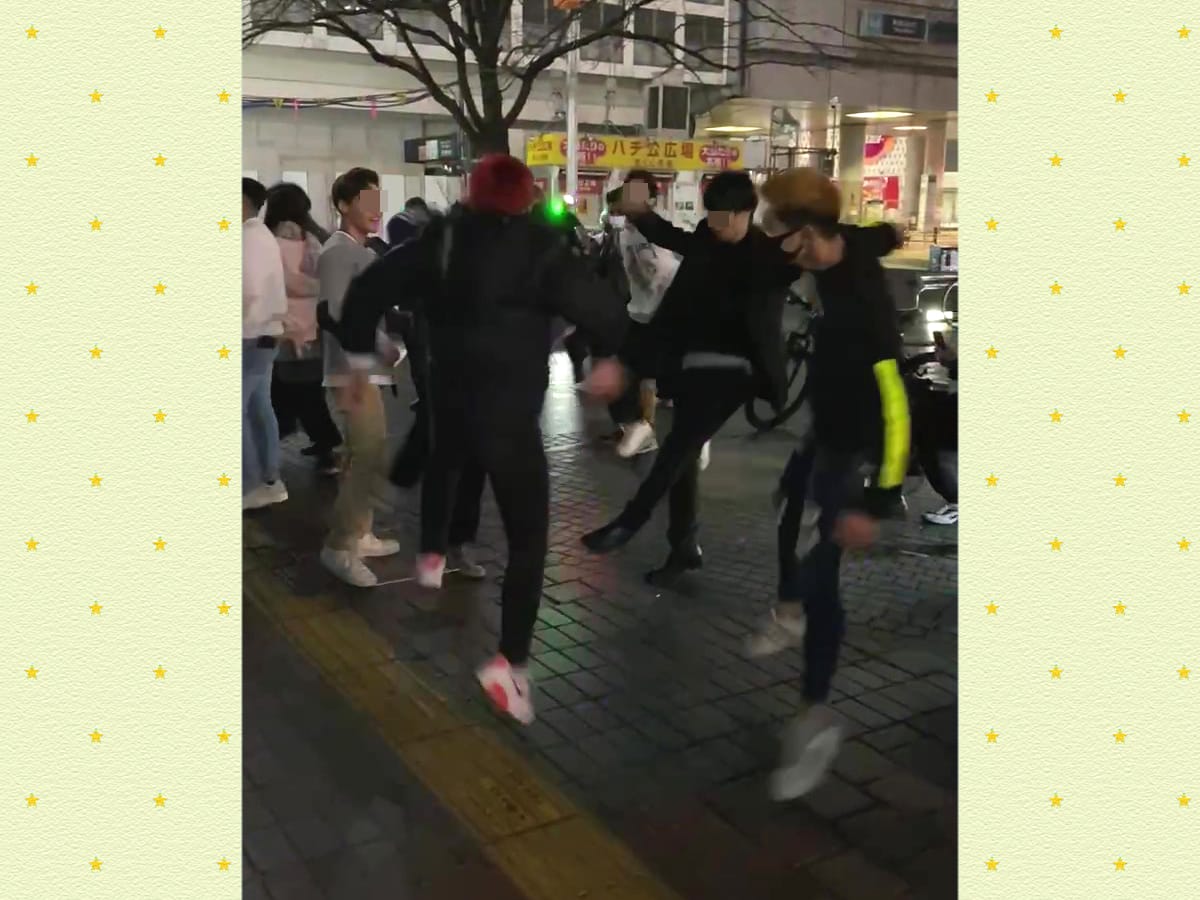

We wandered around the corner to Hachiko, where we found another, even smaller group of revellers jumping around to a Japanese techno outfit. They didn’t last long before they were mobbed by a horde of police officers, who told them they were causing a public disturbance.

Luckily for them, one of their fans seemed well versed in Japanese public order legislation and did his best to defend their right to party. A very reasonable and even-tempered discussion ensued, at the end of which the techno outfit went home.

For a time, I thought the police had put a dampener on the evening’s proceedings, but within ten minutes of their departure, a rival crew showed up and started playing Indian club tunes at full blast. Doubtless cowed by the prospect of having to listen to drunken foreigners and their cobbled-together Japanese language abilities, the police opted to let them be.

So it was that in 2020, the New Year’s Eve celebrations in the best-known meeting spot in the biggest city in the world was dominated by what looked to be an Indian village disco. It wasn’t what I’d been expecting, but all the same, a good time was had by all.

There were several foreign guests. The IT crowd was represented by a couple of young French dudes, the convenience store workers by two Nepalis, who were bemusedly watching their drunken Kazakh co-worker’s dance moves.

When the cold started gnawing at our bones, we wandered up Dogenzaka. There were a few stragglers milling in the side streets, but frankly, no more than you’d expect to find after a wedding party in a typical Indian village.

I was starting to think the virus really had won the day, but at the top of the hill, we came to a nightclub with steamed up plate glass windows. Peering inside, we saw that the place was heaving with young Japanese bopping away and shouting into one another’s ears.

Perhaps this is where the guys from Kokuminshukento went for their after-party? I wondered. I spoke to the bouncer outside the club. He said he was from Guinea. He looked pleased when I told him I was from England. “ENG-land is a land of ENG-ineers, isn’t it?” he said.

“Aren’t they worried about the coronavirus?” I asked him, gesturing towards the young revellers inside. “They don’t care about the virus,” he said with a resigned smile (though I couldn’t help noticing that he adjusted his facemask for a closer fit as he said it).

The club turned out to be as close as we got to a traditional New Year’s send-off. It was quite close enough for me. I was glad to have finally found a group of Japanese people having a good time on the last night of such an anxiety-inducing year. But you won’t catch me revelling with a bunch of strangers in a sweaty nightclub – or at least, not until the government rolls out that vaccine. Happy New Year!