Photo by George Lloyd

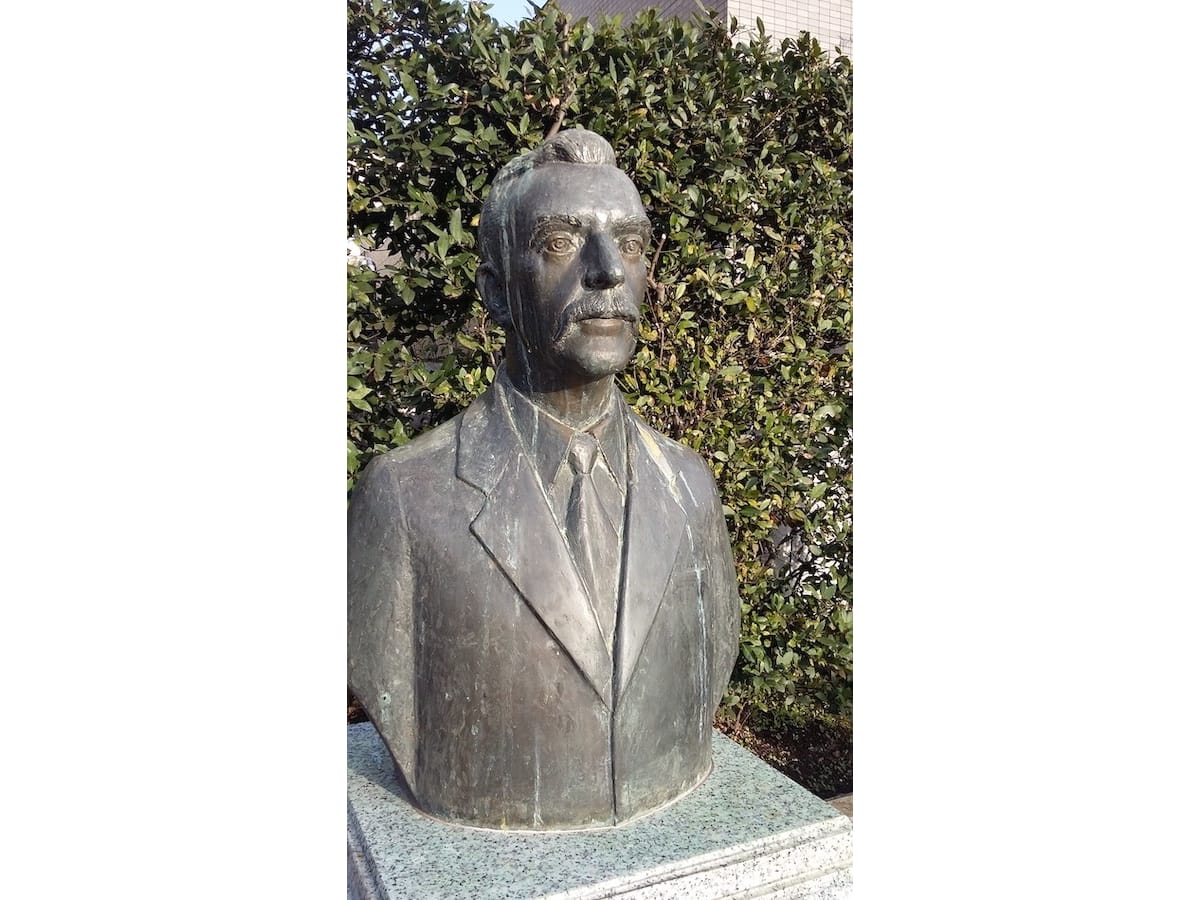

Pondering the archetypal outsider at the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Park in Shinjuku

- Tags:

- Japanese history / Lafcadio Hearn / Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Park / Park / Shinjuku

Related Article

-

Kuge: Japan’s original art snobs have a lot to answer for

-

Japan Railways To Implement Private Work Cubicles And Shared Work Spaces In Tokyo Train Stations For Lateworking Salarymen

-

Shinjuku’s new giant 3-D cat now plays with a giant Roomba

-

Japanese shaved ice master’s gourmet kakigori will make you feel like a billion yen

-

Japanese artist recreates giant 3-D cat at Shinjuku Station with actual cat

-

Feel The Autumn In The Middle Of Tokyo – A Great Spot For A Romantic Date Too!

Lafcadio Hearn, known in Japan as Koizumi Yakumo, was a Meiji-era (1868-1912) writer whose descriptions of Japan had a huge impact on how the outside world viewed a country that was then regarded as the epitome of exoticism.

The Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Park is a small park in Nishi-Shinjuku, Tokyo that has been dedicated to his memory. It's a fitting place to remember him and to consider his impact on western perceptions of Japan, and what it means to be an outsider.

Photo by George Lloyd

Hearn was born on the Greek island of Lefkas, grew up in Dublin, and spent most of his adult life in the United States and the Caribbean. That he should have ended his days as an honoured citizen of Japan is both touching and ironic, for he was a lifelong outsider.

Hearn was a child of empire, and the empire did not treat him well. He was abandoned, first by his Greek mother, then by his Irish father, and finally by his father's aunt, who had been appointed his guardian.

He was shunted between a series of unwelcoming relatives in Dublin and London until the age of 19, when he was given a one-way ticket to New York, with instructions to look up a long-lost relative.

The Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Park has an ornamental garden with Greek flourishes like Doric columns.| Photo by George Lloyd

The relative wasn't much help, but Hearn soon found work in Cincinnati, as a reporter specialising in lurid crimes. Then he moved to New Orleans, where he spent ten years becoming deeply acquainted with the city's French and Creole culture.

Hearn had none of the racial superiority of his father's generation. He was married to a black woman for a time, in contravention of the anti-miscegenation laws of the day. He immersed himself in the lives of the outsiders he wrote about, of whom there was no shortage in the America of his day.

Hearn had the sensationalistic instincts of a tabloid journalist, but his sympathy for those he wrote about, whether the mixed-race slum dwellers of Cincinnati or the mulatto Creoles of Louisiana, was heartfelt. While he made a name for himself as a champion of the “exotic,” the “colourful,” and the “quaint”, how he was perceived says more about his readers than it does him. Seen through less rose-tinted glasses, Hearn was a pioneering popular ethnographer.

In those days, New Orleans was known as 'The Gateway to the Tropics,' and so it proved for Hearn, who in 1887 headed south again. He spent two years on the Caribbean island of Martinique, where he wrote two books and cemented his reputation as a defender of marginalised peoples and cultures.

The park even has olive trees.| Photo by George Lloyd

Hearn spent the last 14 years of his short life (1890-1904) in Japan. He loved Japan and was in awe of it. "The Western mind appears to work in straight lines; the Oriental, in wonderful curves and circles," he marvelled.

Hearn first lived in Izumo, north of Hiroshima, and then in Kumamoto. After marrying a Japanese woman, he adopted her family name and was known thereafter as Koizumi Yakumo.

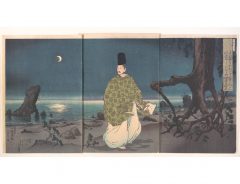

He wrote many popular books about Japan, encompassing ghost stories, fairy tales and travelogues. They allowed him to enjoy a second life as an interpreter of a land that most westerners regarded as the quintessence of exoticism.

A copy of the commemorative plaque outside Hearn's boyhood home in Dublin.| Photo by George Lloyd

But Hearn didn’t just export Japanese culture to the West – he also reinterpreted it for a Japanese audience. Like him, many Japanese thinkers were struggling to find their place in the world during the Meiji era. They found a sympathetic observer in Koizumi Yakumo.

They appreciated his sensitive interpretation of their country, and his writings soon became a much-loved part of the literary canon.

While foreign writers on Meiji-era Japan like Basil Hall Chamberlain and Pierre Loti have been largely forgotten, Hearn's renditions of Japanese folktales are still familiar to every Japanese schoolchild.

Hearn’s major theoretical work is Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation. Published shortly before his death, it is quite unlike any of his previous books. Neither a picturesque travelogue like his Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), nor a collection of retold stories like Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life (1896), it is his only attempt at a scholarly, purely non-fictional study.

It has to be said that Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation doesn't stand up to scrutiny, at least not through a contemporary lens. During his time in Japan, Hearn became a vocal advocate of its imperialistic ambitions, and he was a keen supporter of its wars with China in 1894 and Russia in 1905.

In his defence, it might be said that, like many Japanese nationalists, he was motivated not by a love of imperial aggrandisement per se, but a fear of cultural extinction. The way Hearn saw it, Japan was at risk of being overwhelmed by the European powers and the United States. Unlike the Creole and Afro-Caribbean communities he had written about with such fondness earlier in his career, Japan had a chance to escape its fate, by outdoing the West as an imperialist power.

Well, the less said about that, the better. Contemporary readers are better off sticking to Hearn's descriptions of everyday life and customs in turn of the century Japan. Not only are they beautifully done, but many of them also still ring true 120 years later.

Hearn was keen to stress the cheeriness of Shintoism.| Photo by George Lloyd

Hearn's life was no less poignant than his writings. This Greek-Anglo-Irish American was an unwanted child, a divorced adult, and spent most of his life wandering, physically and spiritually. He was born into the Greek Orthodox faith, educated in Roman Catholic schools, and spent most of his life as an atheist. That he ended his days on the other side of the world and died a Buddhist in a country he evidently loved, must have been some comfort.

If you're looking for somewhere to read one of his books in the spring sunshine, the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Park in Shinjuku is the place for you (you can visit Hearn's grave in Zōshigaya cemetery near Ikebukuro, but there's nowhere to sit).