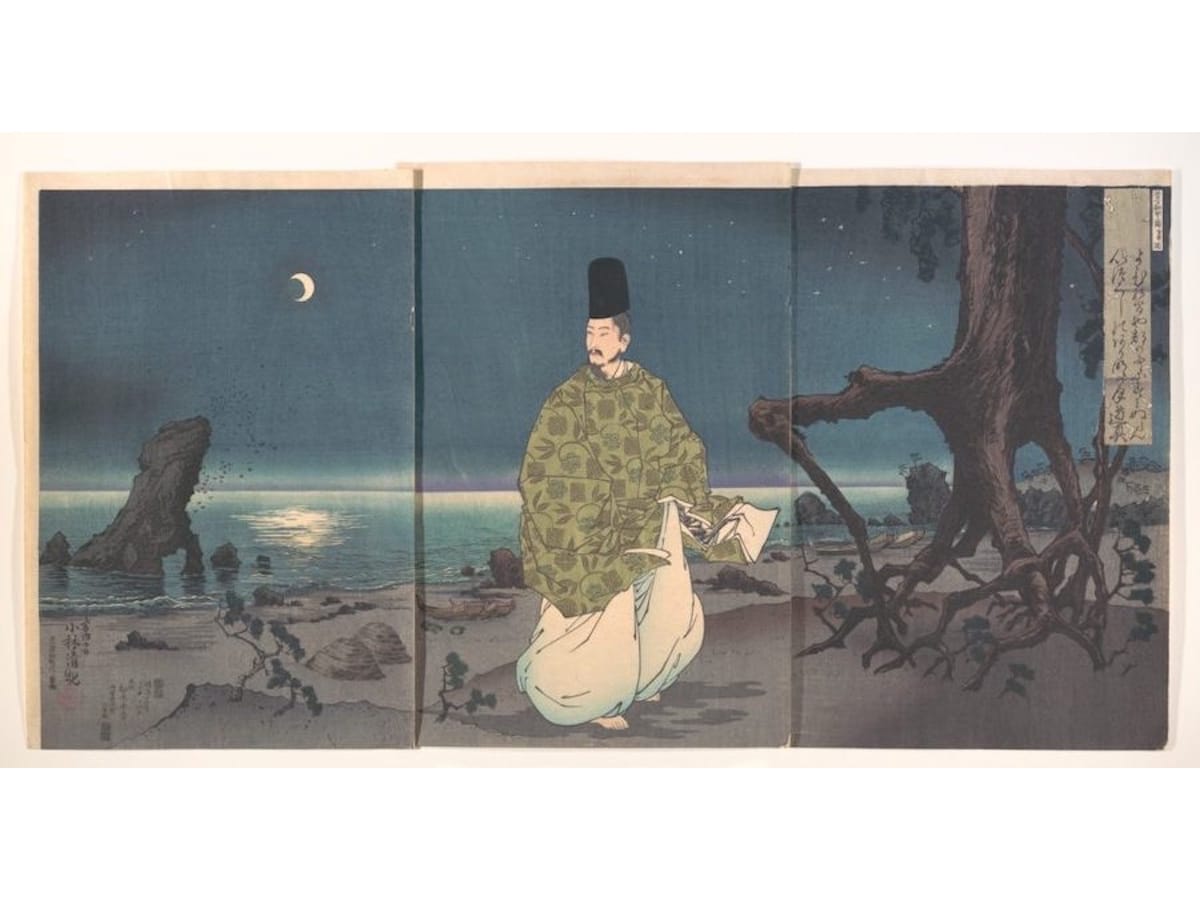

Source: Heian Period Courtier on a Moonlit Beach, by Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915) | © Picryl.com, CC0

Kuge: Japan’s original art snobs have a lot to answer for

- Tags:

- Arts / Japanese history / kuge / snobs

Related Article

-

Japanese Artist Crafts Amazing DIY Sushi Restaurant House For Cat

-

Zoom lecture about Kagawa Toyohiko, “the Gandhi of Japan” on March 30th

-

A pioneering pet lover: the “Dog Shogun,” Tokugawa Tsunayoshi

-

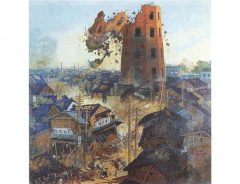

Remembering the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923

-

A potted history of Kabukichō, nightlife capital of Tokyo

-

Hachiko, Japan’s favourite dog, may not have been so loyal to his master after all

Traditional Japanese artistic disciplines like calligraphy, the tea ceremony, and flower arranging are loved and admired around the world. But why are they enveloped in such a suffocating air of veneration? In short, why are so many of their practitioners so snobbish?

The answer lies with the kuge 公家, the nobles who dominated life at the emperor’s court during the Heian era. You won’t find the kuge mentioned in any tourist brochures, but they were Japan's original art snobs. They played a formative role in turning living arts into museum pieces, ossifying them in mindboggling rituals and suffusing them with an impenetrable air of mystery.

A woman practising the tea ceremony. | Georges Seguin (Okki), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The kuge were descended from the Fujiwara family, who ruled every aspect of courtly life in Kyoto during the Heian period. The Fujiwara family controlled the distribution of almost all the important posts at court and reduced the status of the Emperor to that of a puppet. They built fantastical pavilions like Byodoin near Nara and wrote the poems and novels for which the Heian period is famous.

After several hundred years of Fujiwara dominance, there were about 100 families who could call themselves kuge. They were seen as having semi-Imperial status and went to great lengths to distinguish themselves from the buke 武家, or samurai families.

An arrangement of flowers at Meguro Gajoen in 2018. | Gryffindor, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

But in the late 1100s, a great rupture occurred in Japanese history. After hundreds of years of rule by these court nobles, the old system collapsed. The samurai took power and moved the capital from Kyoto to Kamakura, where they established a shogunate that would rule Japan for the next 600 years.

With the samurai overthrow of rule by effete nobles, the kuge lost all their lands and the revenue that they generated. They continued to live in a cramped village around the Imperial Palace in Kyoto, but for the first time in their lives, they had to look for paid work.

After 400 years of writing poetry, they weren’t much use to most employers, so they became teachers of the calligraphy, poetry, and dance they had once practised at court. Naturally, they put great store by etiquette and arcane rituals.

Then as now, the teaching profession didn't pay very well, and the kuge became known for their poverty. But they didn't let their reduced circumstances get them down. Instead, they turned their poverty, knowledge, and overweening snobbery into virtues. Over time, the subdued and the modest became the defining characteristics of the aesthetics of Kyoto, and anything brilliant or demonstrative was scorned.

The Edo era ushered in a long era of peace, and this paved the way for a renaissance of kuge culture in Kyoto. Over time, the kuge developed a system of hereditary franchises, whereby each family purported to be the guardian of ‘secrets’ that had been handed down to the head of the family. Outsiders could only acquire these secrets by paying for them. This was the model for the various ‘schools’ that people went to in order to learn about the tea ceremony, flower arranging, and martial arts.

According to an apocryphal tale, the kuge used to visit their neighbours in Kyoto just before the New Year when all debts are supposed to be settled. “I am terribly sorry,” they would say, “but our family will not have enough money to settle its debts by the end of the year. Consequently, we will have to set fire to our house and flee in the night. I hope that will not cause you any trouble.”

This was a disguised threat, since setting fire to a house in a city as crowded as Kyoto would likely destroy an entire district. So the kuge's neighbours would go around the city with collecting bowls, raise enough money to pay off the kuge's debts, and hand it over to them on the last day of the year.

When the emperor moved to Tokyo in 1868, many of the kuge went with him. Their village around the Imperial Palace in Kyoto was razed to the ground, leaving the open spaces that you see today, and the upper classes of Tokyo got a master class in the importance of kuge concepts like sabi 寂 (elegant simplicity), yūgen 幽玄 (subtle grace) and wabizumai 侘住まい (a quiet life of solitude and contemplation).

To this day, you can still detect the delicate sensibility of the kuge in the schools that people attend in order to learn calligraphy, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony. They typically have a Grand Master, a system of expensive titles granted to students, and elaborate rankings by which their expertise can be judged.

Yet little has been written about the kuge and most students of Japan’s traditional arts don't know the first thing about them. This is a shame, as they explain much of the rarefication and self-conscious pomp that tend to accompany the practice of traditional arts.