Source: mits | © PIXTA

2020 discovery of “possibly Japan’s oldest writing” revealed to be permanent marker ink

- Tags:

- archeology / Ink / inkstone / Japanese writing / Kanji / mistake

Related Article

-

Japan’s Most Beautiful Calligrapher Demonstrates Writing The Most Difficult Kanji

-

The 2018 Japan Kanji Character Of The Year Is “Disaster”

-

Even If You’ve Only Learned Katakana, You’ll Understand This Kanji

-

What Do Japanese People Actually Think About Ariana Grande’s Kanji Tattoo BBQ Blunder?

-

Three manga to learn kanji, katakana and old Japanese as recommended by a Japanese teacher

-

Kanji “trick” for writing complicated Japanese family name draws laughter online

In January 2020, archeologists and scholars researching the history of writing in Japan were excited by the tantalizing prospect that what was "possibly Japan's oldest writing" had been discovered. A Japanese inkstone dating from the mid-Yayoi period (300 BC to 300 AD) excavated at the Tawayama site in Matsue City had markings on it believed to made by a brush and ink.

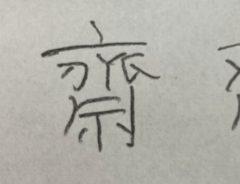

According to the Asahi Shimbun, at a conference held on January 1st, 2020, Takeo Kusumi of Fukuoka City's Buried Cultural Properties Division, stated that the black ink markings were made in a Reisho-tai clerical script from around 0 AD, and that he could make out the kanji 子 and 戊. Yanagida Yasuo, a visiting professor of archaeology at Kokugakuin University who had also studied Yayoi period inkstones, identified the kanji 午, 壬, 戌, and 戍.

However, other scholars who attended the conference voiced skepticism since infrared imaging had not been conducted to confirm the results.

It would seem that the skepticism was warranted.

A meeting of the Japan Society for Scientific Studies on Cultural Properties is scheduled to begin tomorrow, September 10th. As reported by the Yomiuri Shimbun, researchers at the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Prefecture, will present the results of their analysis of the inkstone showing that the markings contained oil and matched the chemical signature of an oil-based permanent marker.

Since the permanent marker was invented in the early 1950s, the markings were obviously not contemporaneous with the inkstone. Instead, according to the researchers, permanent marker ink from labels or other materials were probably transferred during the sorting process.

Kusumi begrudgingly admitted that he had no choice but to withdraw the opinion he made on the inkstone since he could not refute scientific evidence. Moreover, the Matsue City Archaeological Research Department, which owns the stone artifacts admitted that the city "has improvements to make" if the reason for the erroneous opinion was indeed a transfer of ink.