- Tags:

- Japanese Folklore / supernatural / Tono / Yokai / Zashiki Warashi

Related Article

-

Tōno: immerse yourself in the distant past with a visit to the cradle of Japanese folklore

-

Parade of Japanese folklore spirits and demons captured in chilling photography at snow festival

-

Heavy Snowfall In Kyoto Breaks Tengu’s Nose, So Station Staff Give It A Bandage

-

Japanese Demon Stockings Will Have Your Legs Looking Scary Good

-

Japanese artist & illustrator Sakyu creates yōkai monsters from modern objects and phenomena

-

Japan Travel and Folklore: Discover Iwate and go Kappa Hunting in Tono City

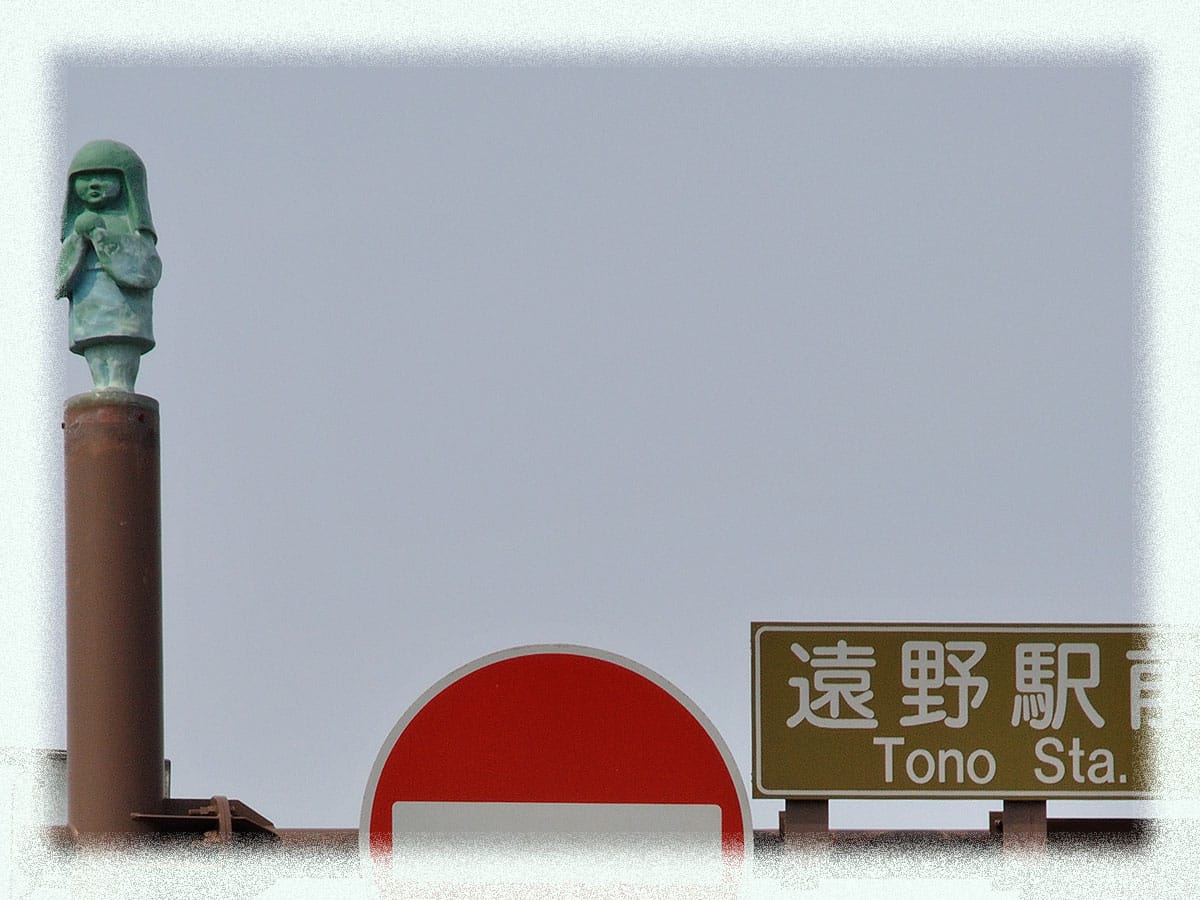

Perhaps you’ve heard of zashiki warashi? They’re pretty famous in Japanese folklore, and still crop up regularly in anime and manga. They’re ghostly children who act as guardians of family homes. There are lots of variations of zashiki warashi across Tōhoku, the north-eastern part of the Japanese mainland, with minor differences in appearance and behaviour, but they are particularly well-known in Iwate prefecture.

The name comes from zashiki (座敷), the guest room in a Japanese house, which usually has tatami flooring, and warashi (童子), an old word for a child used in Tōhoku.

Photo by Nike Keihin, Statue of Zashiki Warashi on Mizuki Shigeru Road in Sakaiminato, Tottori (CC 3.0)

Direct sightings of zashiki warashi are rare. Often the only sign that your house is inhabited by one is a trail of little footprints in the ashes in the fireplace. Some accounts tell of hearing a child’s top spinning all night long, the sound of rustling paper, or children’s voices coming from under the floorboards.

It is said that only members of the family that lives in the house are able to see them, and even they find it hard to make out more than the vague shape of a five or six-year-old child with a blushing red face. Boy zashiki warashi are sometimes dressed in warrior costumes and girls in kimonos.

Zashiki warashi are considered guardians of the house. It is said that a family that has a zashiki warashi living in its house will prosper and grow rich. The desire to keep these friendly little ghosts happy has led to customs like setting out food for them and putting coins under the foundation posts when building a new house.

In many homes, the family’s zashiki warashi will befriend the children of the house, teaching them songs, games, and nursery rhymes. They will also keep elderly or infertile couples company, and these couples often treat the zashiki warashi as if it were their own child.

So far, so kawaii, right? Sadly, this picture of the zashiki warashi only tells half the story. Zashiki warashi have had a makeover in modern times. In manga and anime, they are always depicted as cute kids with freshly washed hair and sweet smiles on their faces. But this anodyne rendition of the ghostly child is a world away from its origins in Tōhoku.

Folklorist Kunio Yanagita collected lots of zashiki warashi stories in Tōno Monogatari, a compendium of folk tales from Tōno, a small town in Iwate prefecture that must have more folk stories than anywhere else in Japan. Far from being adorable cherubs, many of the zashiki warashi he heard described were wild, hairy, brutish characters, given to playing Shinto dirges in the middle of the night.

663highland / CC BY-SA

The ghost children of Tōhoku had good reason to feel gloomy. The north-east has always been the poorest part of Japan (this goes a long way in explaining why its myths and legends have survived for as long as they have). Until the 1930s, famine was commonplace, and killing infants in order to reduce the number of mouths to feed was par for the course.

People wanted to know why they had such rotten luck, and being uneducated in science and basic economics, they turned to the supernatural for explanations. More specifically, they wanted to know why some families flourished, while others floundered. The simplest explanation was that unlucky families had mistreated their zashiki warashi.

In one account from Iwate, a family witnessed a zashiki warashi leaving their home, and soon afterwards, they all succumbed to food poisoning and died. In another account, a wealthy man’s son shot a zashiki warashi with a bow and arrow. Soon afterward, the family’s fortunes collapsed (in hard times, it’s some comfort to know that, in the words of a soap opera popular among poor Mexicans, The Rich Also Cry).

In the area around the Iwate city of Ninohe, 100 km north of Tōno, there is a custom of making up a room with treats and toys for a child who has died. The custom survives to this day, but it began as a tribute to children who’d died at the hands of their parents - which goes to show how widespread the practice was.

The folklorist Kizen Sasaki noted that perhaps zashiki warashi are the spirits of children who were crushed to death and buried in the family home. Infanticide was often called usugoro (臼殺, or ‘mortar kill’) in the Tōhoku region because children would be killed by being crushed by a stone mortar. There was also a custom of burying dead children in the dirt floor of the kitchen, which may explain the belief that you can appease the zashiki warashi living in your house by burying a golden ball under the floorboards.

That is not to say that every zashiki warashi is the spirit of an infant killed by its own parents. Folk beliefs come in all shapes and sizes and interpreting them is not a science. Concerning why zashiki-warashi look like children, you could just as easily point to the widespread folk belief that children act as bridges between the adult world and the afterlife. The kawaii versions of zashiki warashi that you see in manga and anime today probably owe more to the Buddhist figure of the divine child than they do to a desire to forget the bad old days when killing your own child was the standard response to a bad rice harvest.