Source: "Father of Japanese folklore" Yanagida Kunio. | Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tōno: immerse yourself in the distant past with a visit to the cradle of Japanese folklore

- Tags:

- Japanese Folklore / Tono / Tōno Monogatari / Yanagita Kunio

Related Article

-

Zashiki warashi: the mythical children who look after your house

-

Eerie Monsters And Ghosts By One Of Japan’s Last Woodblock Printing Masters

-

Heavy Snowfall In Kyoto Breaks Tengu’s Nose, So Station Staff Give It A Bandage

-

Visiting the Gallery SAJIMA- KAPPA SAN Exhibition in Kamakura

-

Makeup brand KATE reinterprets Japanese heroines with stylish and simple makeup simulator

-

Japan Travel and Folklore: Discover Iwate and go Kappa Hunting in Tono City

Tōno 遠野 in Iwate Prefecture is the home of many Japanese folk tales. The town is the setting for Tōno Monogatari 遠野物語, an anthology of legendary folktales collected and written by Yanagita Kunio 柳田国男 in 1910. Yanagita is considered to be the father of Japanese folklore, and his book has been read and loved by generations of Japanese, young and old for over 100 years.

The creation myths of the Japanese spirit world are all here, although in a country that claims to have eight million gods (yaoyorozu no kami 八百万の神), that can only ever be an exaggeration, as that works out as a god for every 15 people.

A mythical kappa standing by a river. | 竜斎閑人正澄 (Japanese), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Like people the length and breadth of Japan, the people of Tōno used to believe that there were gods living in the natural world around them. A local mountain had a god; the river had a god; the wind had a god.

The people of Tōno have long feared nature and worshipped it, and for good reason. Winters are cold and the snow lies deep on the ground for months on end. They learned to move in harmony with the elements.

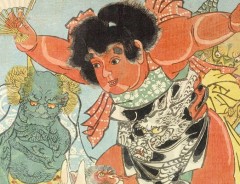

Such were the lives of the people who created and passed on the tales collected in Tōno Monogatari. Among the creatures Yanagita Kunio describes in his collection are the tengu (a long-nosed red goblin) and the zashiki-warashi (a child who protects households).

However, the best-known stories in Tōno Monogatari are the ones about kappa. These half-man, half-frog-like creatures have shells on their backs like turtles, a plate-shaped indentation on top of their heads, webbed hands and feet, and a sharp beak-like mouth.

Kappa live in rivers and streams and were said to protect children from drowning. Kappa Buchi is a riverside spot in Tōno where they are supposed to gather. There is a small shrine next to the stream dedicated to the god of the Kappa. For ¥200, the Tōno Tourism Association will issue you with a ‘Permit for Catching Kappa,’ complete with instructions on how to go about catching one.

A traditional nanbu-magariya , or southern-style bent house. | Tanaka Juuyoh, CC by 2.0 / © Flickr.com

Aside from its wealth of folklore, Tōno is worth visiting for its traditional farmhouses. The nanbu magariya (南部曲がり家 southern-style bent house) is a traditional house with a thatched roof.

Even in the depths of the countryside, few Japanese people live in magariya anymore, but you can visit one in Tōno. Such is the rarity of the Chiba family’s magariya, it has been designated a national cultural property.

It is 200 years old and has thick stone walls quite unlike a typical Japanese farmhouse. In the old days, 25 people lived in the Chiba family’s magariya, including the owner, his family, and their servants.

Another good place to see a magariya and learn about country life as it was lived in the old days is at Tōno Furusato Village. It is a recreation of a traditional village, complete with thatched roof magariya, a lodge where the family used to make charcoal and several waterwheels.

Most of the goods used on the farm at Tōno Furusato Village are made of straw or bamboo. You can try your hand at pounding rice (mochi-tsuki 餅つき) and making soba noodles. You can also listen to a storyteller (kataribe 語り部) tell stories about the many gods that the old-timers used to believe lived in the region.

A view of Tōno Furusato Village. | Tanaka Juuyoh, CC by 2.0 / © Flickr.com

Another living museum you can visit in Tōno is Denshōen (伝承園). Among the buildings is the magariya of the Kikuchi family, which is a great place to see the lifestyle of a traditional farming family up close. There is a restaurant serving delicious local dishes and you can make your own crafts and listen to folktales here too.

Here are the websites for Tōno Furusato Village and Denshōen.

Tōno is in Iwate prefecture in northeastern Japan. The town is located an hour from Shin-Hanamaki station on the JR Kamaishi line.

For information on how to get to Tōno and places to stay in the town, see the Tōno Tourism Association’s website.

If you’d like to find out more about Kappa, including instructions on how to catch one, see my previous article, ‘Kappa: a water imp among the cutlery and tableware of Kappabashi’