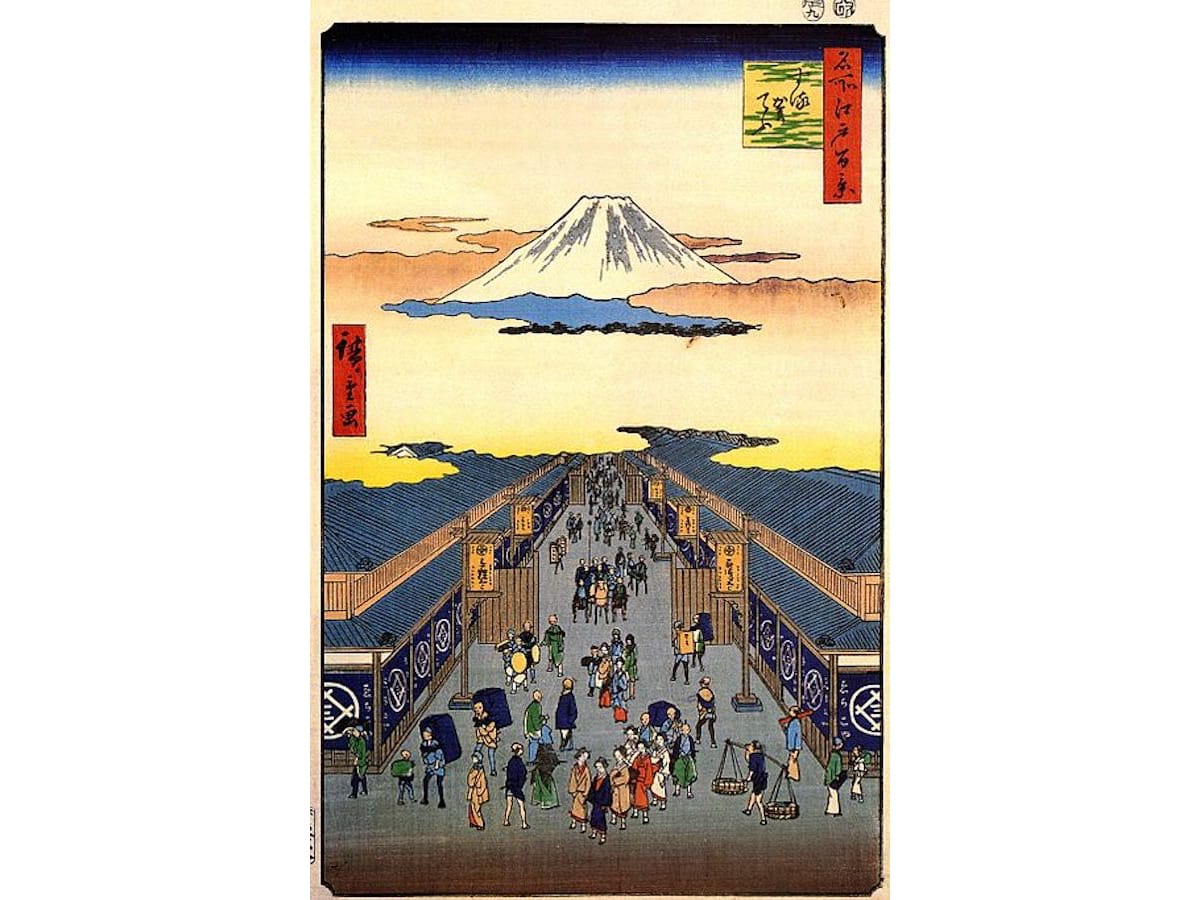

Source: An ukiyo-e print by the artist Utagawa Hiroshige with Mount Fuji and Echigoya as landmarks. Echigoya is the former name of Mitsukoshi, whose headquarters can be seen on the left-hand side of the street. | Hiroshige, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How Tokyo’s department stores got their big start

- Tags:

- Department stores / Japanese department stores / Tokyo

Related Article

-

The street art scene in Tokyo

-

Tokyo Hit By Heaviest Snow Storm In Four Years And Some Actually Enjoyed It

-

Jesus Cafe Takes Japan’s Themed Restaurant Trend to New Blasphemous Levels

-

Photographer KAGAYA Shows Off The Glowing Wonder Of Tokyo In One Shot

-

Waiters With Alzheimer’s Serve Up Meals At Tokyo’s “The Restaurant that Messes up Orders”

-

New Studio Ghibli Short Animation by Hayao Miyazaki to be Screened at Ghibli Museum

The first modern department store in Japan was Mitsukoshi, which was founded in 1904. But in common with most of the country's most venerable department stores, Mitsukoshi 三越 has its roots in the Edo period, starting life as Echigoya 越後屋, a kimono shop in Nihonbashi that first opened for business in 1673.

Matsuzakaya 松坂屋 has an even longer history, dating from a kimono shop in Nagoya that first opened in 1611. Takashimaya 高島屋 also began as a kimono shop, in Kyoto in 1831, while Isetan 伊勢丹 started out in Kanda in 1886.

The Ginza Mitsukoshi store by night. | Kakidai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Were it not for the advent of the railways, these retailing giants would have had Tokyo's retail market to themselves. But the urban development of Tokyo in the 20th century clustered around the six biggest train stations on the Yamanote line - Shibuya, Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, Ueno, Tokyo and Shinagawa - and from the off, the railway companies wanted a slice of the retailing pie.

The Yamanote line encircles the centre of the city and each of these nodes on the line was the termini for a private railway line, which stretched out into the suburbs like the tentacles of an enormous octopus. To exploit the captive market passing through their stations every day, each of the train companies built a department store outside the main entrance to its station.

These newcomers were soon giving the city's traditional department stores a run for their money and in time Shibuya came to be dominated by the Tokyu company, which ran the railway lines serving the western suburbs, Shinjuku by the Keio and Odakyu companies and Ikebukuro by Tobu and Seibu.

Matsuzakaya in Ueno Hirokoji c. 1930. | http://www.kinouya.com, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s easy to forget how very un-Japanese a department store must have seemed at the beginning of the 20th century. In dry goods stores, the forerunners of the department stores, the customer would sit barefoot on the tatami mats while one of the all-male staff went to the go-down to get the goods she wanted and then brought them back to the shop to show them to her.

This all changed with the advent of the department store. Now customers exchanged their shoes for slippers on their way into the store, the goods were all in gleaming showcases and all the staff were female. Having thousands of pairs of shoes to deal with, staff often got them mixed up, and many customers preferred to go to smaller shops.

But the trend towards bigger retail spaces was inexorable. In 1914, Mitsukoshi expanded into a new Renaissance-style building in Nihonbashi. It had elevators, escalators, central heating and a roof garden and was said to be the world's largest department store east of the Suez Canal.

The department stores were heirs to the markets that sprang up around the city’s shrines and temples. They both drew in the crowds by offering culture and entertainment alongside the merchandise. In the Taisho period, Mitsukoshi even had an in-house boys’ band (which is worth remembering when people accuse today's boy bands of being 'too commercial’). It was said to be the first non-official band in the country. The boys wore red and green kilts and quickly became the talk of the town.

After the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, Tokyo's department stores were rebuilt and expanded in size. The new stores abandoned the rule whereby customers had to take off their shoes and change into slippers when they came inside. Advertising took off, and “the old, subdued harmonies of brown and grey surrendered to a cacophony of messages and colours” (in the words of Edward Seidensticker, the city's foremost foreign historian).

Before the earthquake of 1923, women didn’t often eat out in Tokyo, but the department store dining room allowed them to overcome their reticence to be seen eating in public. Gradually, convenience topped etiquette, and men and women began to eat at western-style tables. They no longer took their shoes off, often kept their hats and coats on and sometimes even ate standing up.

In the Meiji period, women had taken over nursing and the telephone exchanges, and a handful had started working in shops, but the department stores were among the first employers in Tokyo to take on women en masse. Where they led, others followed. In the 1920s, ‘red-collar girls’ – female bus conductors – made their first appearance, and on the new Showa-dori, women began pumping gas in the gas stations for the first time.

In the 1930s, the main rival to Mitsukoshi in Nihonbashi was Shirokiya 白木屋. There was a terrible fire at Shirokiya in 1932. Fourteen people died, most of them shop girls who fell to their deaths after trying to hold a rope with one hand, while using the other to stop their skirts from flying up over their heads. In those days, female shop staff wore Japanese dress and no knickers. After the fire, Shirokiya required that their female staff wear undergarments and started paying them subsidies to wear western dress, which was considered safer.

The Shirokiya department store was burned out again as a result of the fire-bombing of Tokyo in 1945. The company did not survive, but their store incubated Sony, which started out as a radio repair business in the burned-out shell of the Shirokiya building.

In the post-war years, Tokyo's department stores became vast retail emporia, bastions of cultural conservatism, and guardians of good taste for millions of Japanese as they embraced the middle-class urban lifestyle. Due to their roots in the Edo period, they have always carried more domestically produced artisanal goods, and fewer imported goods than you’d see in a European or American department store. Most of them still have sections devoted to kimono and traditional Japanese crafts, including pottery and lacquerware.

Tokyo's department stores also tend to offer a wider range of services than you'd find in a European or American department store, such as foreign exchange, travel services and concert tickets. There is usually a grocery and food court in the basement level, a garden and children's play area on the roof and many of them also have art galleries.

It is this all-embracing attitude to the retail trade that puts department stores at the heart of public life in Tokyo. Since the 1980s, they have been facing stiff competition from supermarkets and convenience stores and are gradually losing their presence in the shopper's imagination. All the same, they remain standard bearers for the Japanese understanding of the good life.