- Tags:

- Heiwa Kinenkan / Japanese history / Japanese soldiers / Museum / war / World War II

Related Article

-

How we became modern: a trip to Tokyo Advertising Museum

-

Japan Guide: Visit Otaru during winter

-

Japanese retail company’s offer to welcome 100 Ukrainian refugee families moves people to tears

-

Tokyo’s New teamLab Museum Will Immerse You in a Digital Art Wonderland

-

Watch How the Edo Period Shaped Today’s Tokyo with Video Celebrating Edo-Tokyo Museum’s Reopening[PR]

-

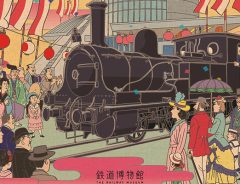

Omiya Railway Museum Showcases Dawn of Railroads in Japan Until Sept. 30

Don't be put off by the cumbersome name. The Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates is a fascinating place. Though little-known, and somewhat tucked away halfway up a skyscraper in Shinjuku, it is the city's best museum about Japan's experience of World War Two.

The museum comes in three parts. The first is about the soldiers who went off to fight overseas. The second is about soldiers detained in Siberia at the end of the war. The third is about post-war repatriates, the civilians who found themselves stranded in foreign countries at the end of the war.

The museum aims to "deepen people's understanding of the hardships suffered by those who experienced the war." It does this through well-chosen objects, photographs and dioramas, which really bring home the war as it was lived by the millions of soldiers and civilians who took part in Japan's ill-fated attempt to build an Empire in the Far East. Here are some of the highlights.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Japan had a system of military conscription and any male over the age of 20 was expected to sign up to go and fight. Japan sent more than 10 million soldiers to battlefields across East Asia.

The picture above shows a replica of a 'Good Luck Flag', which was carried by soldiers when they left for the front. The Rising Sun motif in the middle of the flag is decorated with the kanji for strength: 力 chikara. Soldiers would carry it with them before they were posted overseas. It was customary for soldiers to ask their neighbours to add their blessing by writing the same character 1000 times around the edge of the flag.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Japan occupied Manchuria between 1931 and 1945. This picture shows a copy of the Textbook for the Brigade of Patriotic Youth for the Development of Manchuria and Mongolia.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

This sketch was made by a Japanese soldier who was posted to Burma (modern day Myanmar). It is one of 60 sketches he made of the surrounding countryside and wildlife during the twelve months he was stationed as a guard at a prisoner of war camp.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Japan declared war on China in 1937. This is one of the propaganda leaflets that the Japanese Imperial Army dropped over China by. It shows the plentiful food available to Chinese troops who surrendered.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

This is one of the propaganda leaflets dropped over Japan by the United States Air Force in the closing years of the war. On one side is a copy of a 10 yen note, which was designed to attract the attention of passers-by. On the other side is a message urging the Japanese people to surrender.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

The USSR only declared war on Japan in August 1945. The Red Army moved into Manchuria and Korea and captured hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers. This is a communique issued by the Soviet Politburo authorising the transfer of 500,000 Japanese prisoners of war to detainment camps in the Russian Far East.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

The Soviet communique was signed by Josef Stalin, the leader of the wartime USSR, and is dated August 1945.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

The detainees were put to work farming, mining, logging, and building railways and roads in the Russian Far East. This is a scale model of one of the scores of camps built to house Japanese prisoners of war.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Temperatures in the Russian Far East regularly drop to minus 30 degrees Celcius in the winter months. Clothes were in short supply, so detainees had to make their own to ward off the extreme cold. These socks were made by a detainee in a Soviet POW camp, using yarn supplied by Red Army authorities. Detainees also had to make their own needles and thread.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Prisoners even had to make their own eating utensils.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Two things there was no shortage of, however, were white birch and time, as these beautifully crafted wooden eating utensils show.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

Food was scarce in the camps. In this diorama, prisoners keep a close eye on a fellow detainee as he measures and meticulously cuts up a loaf of rye bread.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, 3.2m Japanese civilians found themselves dispersed across an empire that no longer existed. In April 1946, the Japanese government began organising passenger ships to bring them home, but it wasn't until 1956 that the last repatriate ship from the USSR arrived back in Japan.

This diorama shows life below deck aboard one of the passenger ships that brought Japanese civilians back to Japan from Huludao (Kurotou) in Manchuria. Many of them returned home emaciated, broke and propertyless.

Photo by George Lloyd, with permission from the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates

This Handbook for Returnees was issued to demobilised troops and repatriated civilians by the Ministry of Education upon their arrival in Japan. It was subtitled For a New Departure. It explains the new laws and institutions established by the Occupation Authorities.

You will find the Memorial Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Post-war Repatriates on the 33rd Floor of the Shinjuku Sumitomo Building. The address is 2-6-1 Nishi-Shinjuku. Admission is free.

For details, see their official website or call 03-5323-8709.