Source: ottmarliebert.com from Santa Fe, Turtle Island, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What is wabi sabi?

- Tags:

- Japanese Art / Japanese culture / wabi sabi / Zen Buddhism

Related Article

-

These Japanese Toilets Are Way Too Beautiful For Their Own Good

-

New Exhibit In Tokyo Explores The Fantastic Work Of Kyōsai–One Of Japan’s Greatest Artists

-

Japanese Sumi-e Artist Brings Rurouni Kenshin Characters To Life With Brilliant Ink Paintings

-

Space Glass: Japanese Artist Creates Beautiful Galaxies And Solar Systems In Glass Pendants

-

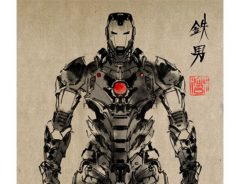

Traditional Japanese Ink Wash Iron Man Is Here To Save The Future And Ancient Past

-

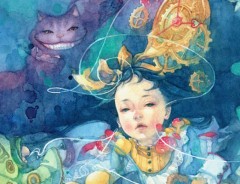

Alice In Wonderland Re-imagined With Japanese Artwork: Gorgeous Watercolor

Wabi sabi 侘び寂び is a Japanese concept that often has foreigners scratching their heads in bafflement. The first part of the expression - wabi - refers to the bitter-sweet pleasure of being alone. It refers to the serenity that comes from detaching yourself from society, and its endless striving for wealth and status.

The second element is sabi, a reference to the noble veneer that the passage of time lends to people and objects. It asserts that while time affects people no less than it does objects, the essence of both remains the same.

Wabi sabi is most often used to describe art forms. It is about imperfection; about appreciating things all the more because you know that they are transitory and will pass and that nothing on earth is forever. Wabi sabi embraces anything that reminds the viewer of the natural world. It spurns uniformity for what is asymmetrical and rough. Flaws and imperfections are good. Small scale and artless is good. Anything that is natural and unself-conscious is good.

This modest, sentimental way of looking at the world is a long way from classical western aesthetic norms, which have their origin in Ancient Greece and Rome. Classicists believe that by using our rational faculties, we can strive for perfection. Classical art strives to be monumental, spectacular, and enduring, and because idealism is a cherished part of being young, youth is also a key part of the classical mindset.

The Zen garden at Ginkakuji temple in Kyoto. | Paul Mannix CC by 2.0, © Flickr.com

Wabi sabi, on the other hand, has its roots in Zen Buddhism, which teaches that wisdom is attained by coming to terms with, rather than trying to overcome, human limitations. Zen Buddhists believe that by making nature the focus of meditation, they can make peace with the emptiness at the core of human life. So wabi sabi is essentially a religious term, part of a tradition of monastic austerity that can be seen in countries around the world. It is unabashedly humble, and values all that is simple, plain, and unadorned.

The quintessential expression of wabi sabi is the tea ceremony. The ritualised preparation of tea also has its roots in Zen Buddhism, for monks used to drink tea to help them stay awake during their long meditation sessions.

The father of the modern tea ceremony was Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). He turned the preparation of tea into an extension of prayer, but he also reassessed the fine Chinese porcelain he drank his tea from. Classical Chinese ideals were also centred on striving for perfection. Japanese pottery, on the other hand, was more rustic and often had flaws in the glaze. Rather than reject these imperfections, Sen no Rikyu took them to heart.

There is a famous story about how Sen no Rikyu got one of his apprentices to clean his teahouse. The boy swept it until the place was spotless. When his master saw what he had done, he shook a nearby maple tree so that the leaves fell onto the freshly swept path. This combination of intention and blind chance, the striving for perfection, and the randomness of the end result, is at the heart of wabi sabi.

The Site of Sen no Rikyu's residence in Sakai, Osaka prefecture. | 663highland, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What's unusual about Japan is the extent to which the feudal nobility was influenced by the ideals of monastic life. In a society as hierarchical as feudal Japan, Zen Buddhism was a revolutionary way of thinking, for it suggested that wisdom was attainable by anyone, regardless of rank or status. Moreover, it insisted that wealth couldn't buy anything truly meaningful and that there was nobility in poverty.

The wabi sabi ideal is not just unambitious. It spurns everything that is modern, or urban, and encourages people to immerse themselves in the natural world instead. So what room is there for wabi sabi in a culture as regimented and orderly as that of modern Japan?

From a distance, Tokyo looks like so many blocks, of different shapes but all cast from the same mould making machine (well, no one said that the titans of big business and government bureaucrats who created the modern city were into wabi sabi). Look at the city close up, however, at its shops and houses, and the details will indicate the opposite: clothes, books, magazines, graphics that are much more individualistic and expressive. The merchants of Japan might not be into wabi sabi, but many of its artists, designers, and thinkers are.

To really embrace wabi sabi is too much for most people. By and large, they don't seek respite from modern life in the natural world, or in appreciation of what is fleeting or humble. These days, they are more likely to retreat to a child's world of bright colours, smiling faces, and simple pleasures. The passivity, humility, and austerity that wabi sabi teaches throw a spanner in the works of city life, with its sociability, love of activity, and accumulation.

Yet even in modern Tokyo, many people's approach to life is still informed by the principles of wabi sabi. In their consideration for others, personal modesty, and lack of ego, they remain Buddhist to the core. The aesthetic and philosophy of the monastery pervade everyday life in Japan. It is ritualistic, codified, both paternalistic and unforgiving.

There's something about the Othering of the East that makes westerners think that every Japanese person carries mystical concepts like wabi sabi in her head from birth. Part of their obfuscation lies in suggesting that concepts like wabi sabi are beyond rational analysis while being understood by all Japanese.

By this reckoning, wabi sabi cannot be grasped, much less critiqued or modified. This might make for a stiflingly conservative approach to culture, but no one said it had to make sense. Indeed, Zen Buddhists will tell you that's the point: to stop trying to make sense of things. In Japan, all the best ideas are beyond definition. It's what makes an idea good; it has to be mystical, beyond rational comprehension.

Letting go of your conscious mind is pretty difficult for a modern westerner, for the conscious mind is what we most prize. But the idea that the essence of life is beyond language is a key part of Buddhism, which encourages its followers to stop thinking and instead use their intuition and experience as a guide, for that is the only way to leave the ego behind.