- Source:

- © JAPAN Forward

- Tags:

- Emperess Masako / imperial family / Jūnihitoe / kasane / Kimono

Related Article

-

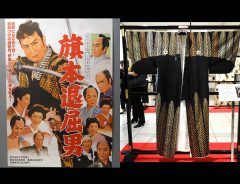

See Exciting Samurai Film “Hatamoto Taikutsu Otoko,” Splendid Kimonos Worn by Lead

-

Experience All the Charm of Japan in a Traditional Ryokan Hotel[PR]

-

[Kimono Style] International friendship and style showcased in FashiComm

-

Japanese Wedding Company Is Renting Out Stunning Dresses Made From Vintage Kimonos For Brides-To-Be

-

What It’s Like To Get The Full Kimono Wearing Experience in Kyoto

-

Vote For Your Favorite Design Of The First Ever Evangelion Kimono Series

Sheila Cliffe, for JAPAN Forward

The recent enthronement ceremony of the new Emperor and Empress has been a talking point in the last few weeks, with dignitaries attending from all over the world, many in their own national dress.

The sumptuous dress worn by Empress Masako attracted the attention of news outlets both in Japan and abroad. As is Japanese tradition for formal imperial events, the clothing worn is that of the courtiers of the middle ages, the Heian era in Japan.

In this installment, I will discuss the history of the garment and my personal experience in wearing it.

What is the jūnihitoe?

The jūnihitoe 十二単 is a woman’s garment considered to represent the pinnacle of loveliness in Japanese traditional dress.

The name literally means “12 layers,” but there could be fewer or even more. Twelve is meant to signify there are a great many. Empress Masako’s jūnihitoe was a combination of various reds, a sliver of purple, some leaf green, all topped with a white brocaded coat.

Photo by © Sankei Shimbun | © JAPAN Forward

For her wedding she also wore the jūnihitoe. At that time, it was a combination of layers of red and yellow with a green brocade jacket on top.

While many non-Japanese like to go to a henshin stajio (make-over studio) to dress up as a maiko or an oiran and have their photographs taken, I have to admit that my own imagination is captured more by the jūnihitoe.

Background of the jūnihitoe

How and why did such an incredibly complex and impractical-looking garment come into existence? What purpose does such impractical clothing serve?

As there are no extant versions of the clothing, our information comes from the illustrations of the Tale of Genji (early 11th Century), written by the courtier Murasaki Shikibu, and from other women of the Heian court who indulged in writing novels and diaries. Also, the jūnihitoe is pictured in scrolls that show scenes from The Tale of Genji.

While men of the period are sometimes seen playing kemari 蹴鞠 (a kind of football) and moving around outside in the pictures on these scrolls, women are almost always seen languishing in a little heap on the floor, surrounded by huge mountains of cloth and leaning forward considerably. Written records describing the correct kasane 襲 (layering) for various seasons do exist. This was studied in detail by Lisa Dalby and shared in her book Kimono (1993, Yale University Press).

In this period in history, the Japanese were already weaving complex silk patterns, largely learned from China and Korea, but the technique of dyeing patterns were still in their infancy. Tie-dye techniques were almost certainly known, but rather than reading motifs, the courtiers read the kasane combinations. These combinations usually bore the names of plants and flowers and were changed seasonally. As there were 72 seasons in the traditional calendar, there was a lot of changing of clothes going on.

Practical explanations for this clothing fail, as such a system was not worn by men. Neither was it for outside socializing, as women were rarely permitted to leave their rooms; when they did, they would ride in ox carts with screens on the windows.

Heian women were protected from the eyes of others at all times. If they were visited by a man, he would get only a glimpse of hemlines and sleeve edges as the woman’s face would be hidden by hanging screens.

According to the style of the day, women also grew their hair long, had their faces painted white, and their eyebrows shaved and redrawn halfway up their foreheads.

(...)

Written by Japan ForwardThe continuation of this article can be read on the "Japan Forward" site.

[Kimono Style] Jūnihitoe: Empress Masako’s Sumptuous Enthronement Dress