- Tags:

- Edo / Japanese history / Tokyo / urban planning

Related Article

-

Watch How the Edo Period Shaped Today’s Tokyo with Video Celebrating Edo-Tokyo Museum’s Reopening[PR]

-

Top 7 Pancake Houses In Tokyo Serving The City’s Best Pancakes

-

13 Layer Matcha Parfait is a Tall Glass of Japanese Sweet Perfection

-

Stay cool this summer with this citrus infused menu from GODIVA café Tokyo

-

Japan’s Most Beloved Bear Makes This Tokyo Bar Easy To Enter, Hard To Leave

-

Inside Tokyo’s New Pokemon Cafe: Bask in Pikachu’s Yellow Glory

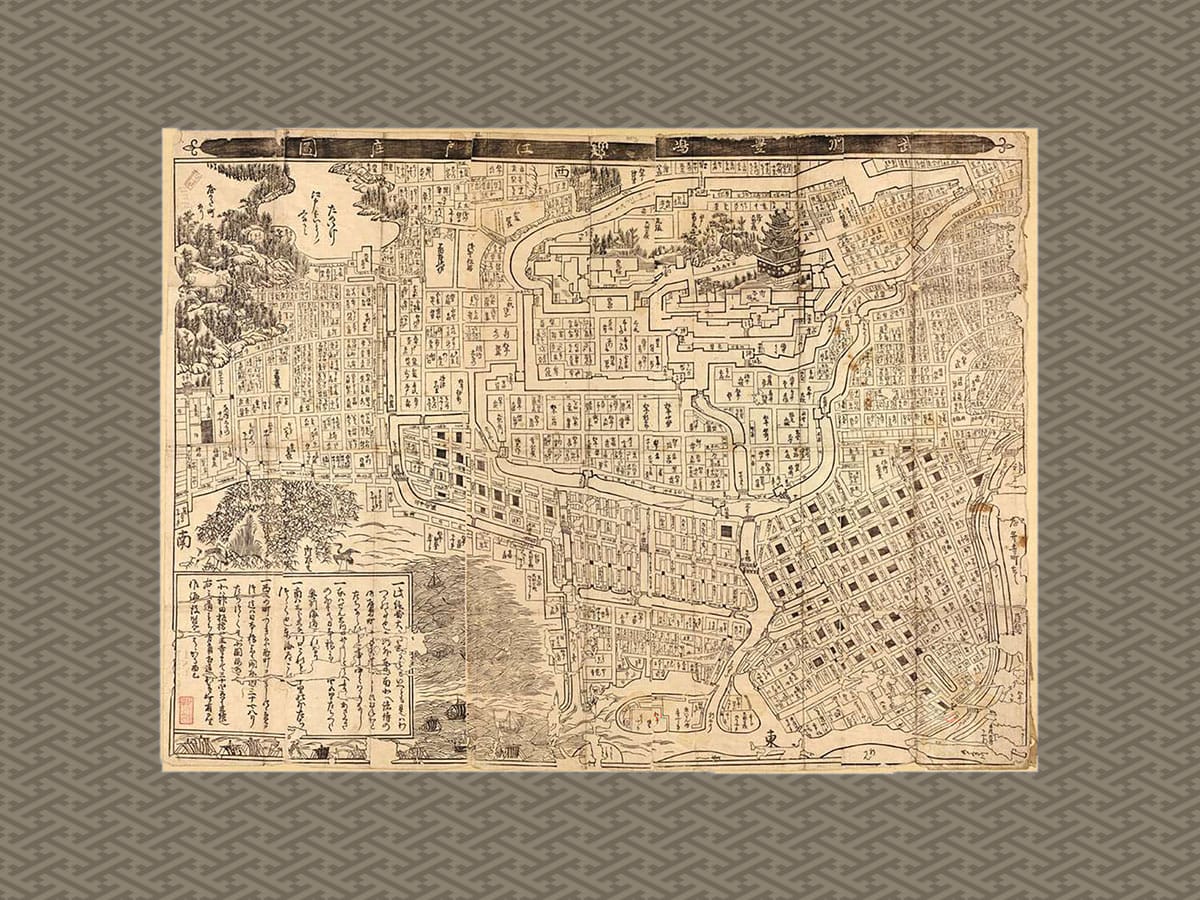

Tokyo is built on the site of the old city of Edo. There are few traces of the old city, but the street pattern of Tokyo is much the same, so the old city lives on in the new as a kind of ghostly template.

How did Edo start out and what did it look like? Until the early 16th century, it was little more than a fishing village in marshland at the mouth of the River Sumida 隅田川. There had been a castle on a promontory overlooking the village since Heian times (794-1185), but it was only after the Tokugawa shogun relocated to Edo that it began to grow.

Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 unified early modern Japan. He recognised the strategic advantages Edo offered, being on the easternmost part of the Musashino Plain 武蔵野 and made it the stronghold of his government. He built a huge new castle on the promontory and dug a moat to protect it from attack.

Nihonbashi's highway distance marker, marking the beginning of the five routes leading out of Edo to the provinces. | Fg2 at en.wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tokugawa Ieyasu developed the land to the east of the castle as farmland to produce crops to supply his castle. A town took shape, and as it grew, he had his soldiers fill in the surrounding marshland and reclaim more land from the sea.

This reclaimed land became the Low City, where the town’s merchants and artisans lived. Like Kyoto, the country’s former capital, it was built according to the grid pattern of the classical Chinese city. The Japanese version wasn’t quite as orderly as the Chinese, for it was actually built on not one, but a series of grids, and they tended to be a bit messy at the edges.

The Low City had two poles: the first was Nihonbashi 日本橋, where the merchants had their warehouses, and the second was Asakusa 浅草, site of the city’s biggest temple, around which clustered most of the business of entertainment. Both districts were crisscrossed by waterways so that goods could be easily moved around the city.

1865 photo of the Tōkaidō road (東海道, eastern sea route), the most important of the Five Routes of the Edo period in Japan, connecting Kyoto to Edo. | Felice Beato, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Determined to achieve total control over Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu introduced a system called sankin kōtai (参勤交代), whereby all the country's feudal lords (大名 daimyō) had to spend every other year in Edo. Even when they went back to their territories, he insisted that their wives and children remain in Edo, a ransom policy designed to deter them from attempting to overthrow him.

Tokugawa Ieyasu reserved land to the west of Edo castle for these daimyō. Unlike the Low City, this area was hilly and more like a country village, with streets that followed the ridges of the hills, animal tracks or the boundaries of rice paddies. It became known as the High City. The daimyō built spacious villas set in large estates in the hills of Akasaka 赤坂, Yotsuya 四ッ谷 and Kōrakuen 後楽園, while the artisans, farmers and labourers who served them lived in the valleys and along the bigger roads.

Depending on the season, Edo was either a sea of mud or a cloud of dust, for most transport was by water and few of its streets were paved. Five highways - the gokaidō 五街道 - led out of the city to the provinces. Each was guarded by a gate, and these became the way stations of Shinbashi 新橋, Shinagawa 品川, Shibuya 渋谷, Shinjuku 新宿 and Senjū 千住. Shibuya and Shinjuku were just villages and only became important in modern times.

By the early 18th century, Edo had a population of over a million. Whatever the season, it would have been a dark city, for all of its houses were made of unpainted wood. Affluent merchants roofed their houses with dark tiles, while poorer people’s houses and shacks had shingled or thatched roofs.

Being a wooden city, Edo was a tinder box wanting for a spark, and every few years, a swathe of the city was burned to the ground. The townspeople came to regard these conflagrations with resigned indifference. They called them ‘Edo flowers.’

You can still see the vestiges of the old daimyō estates – the Mito Tokugawa 水戸徳川 estate in Koishikawa 小石川, for example, became the site of an arsenal, and then the Kōrakuen amusement park and Tokyo Dome. Many of Edo's shrines and temples, which extended in a great arc around Edo castle, have also survived. They were set in relatively spacious grounds, so they acted as firebreaks, sparing them from the flames that ravaged the rest of the city.